By Ray Glier, Georgia Recorder [This article first appeared in the Georgia Recorder, republished with permission]

May 11, 2022

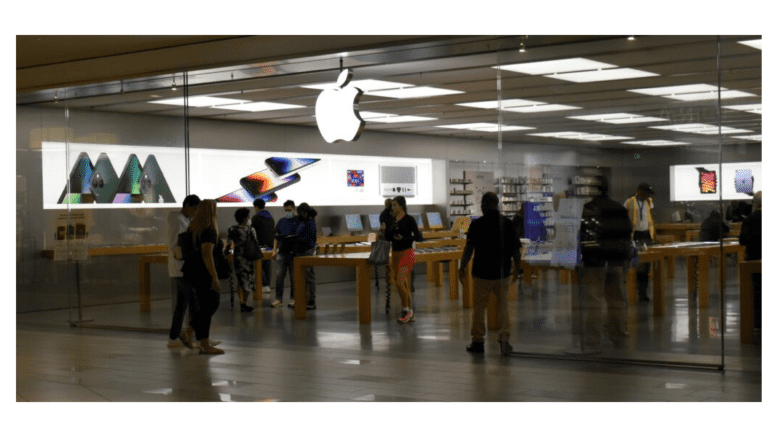

Inside the Apple store at Cumberland Mall, business is brisk on a Thursday afternoon. There is not a whiff of discontent among the retail workers judging by the demeanor of the staff. Before you can walk from the front of the store to the back of the store, three cheerful Apple workers want to know how they can help you.

This does not have the made-for-Hollywood look of a sweat shop begging for collective bargaining action by employees. Apple says it pays workers at least $20 an hour and the culture of the place seems buoyant.

Still, June 2-4, Apple workers at the Cumberland Mall location will hold a public vote on whether to collectively bargain with the company under the banner of the Communications Workers of America.

The legal and persuasive heft of Apple, which is the most valuable company in the world, is formidable, but it is not the antagonist the workers should be most concerned about.

This is the South and the South has been unkind to organized labor for decades.

“I think an important point with regard to unionization is that the political legal landscape across states varies dramatically,” said Matt Knepper, assistant professor in the Department of Economics at the Terry College of Business at the University of Georgia.

“In the northeast, they’re more pro-labor. And the biggest way in which this matters for unions is that in the northeast, by and large, the states do not have right-to-work laws. In the South, particularly the Southeast, right-to-work laws are very prevalent.”

The state of Georgia passed its right-to work-law in 1947, which prevents a union from requiring non-members to pay fees as a condition of employment. The “free-riders” mean the union has less funding and less clout, Knepper said, so it has been historically more difficult to organize unions in right-to-work states.

“I would be surprised if this union fervor that is sweeping parts of the country will be able to sustain itself in a state like Georgia,” Knepper said.

Unionization filings have increased by 57% in the U.S. the last six months, according to data from the National Labor Relations Board. But partisan politics, so invasive in every corner of society, can tamp down the percolating labor movement, especially south of the Mason-Dixon Line, and north of it, as well.

The South is dominated by Republican-leaning voters and Gallup polling data shows that nationally while 56% of union members identify as a Democrat, just 39% of union members identify as Republican. You have to think in Republican-rich states, like South Carolina and Alabama, and in a battleground state like Georgia, the percentage of Republicans who ID as pro-union is even lower.

Indeed, just examine the union vote at a Bessemer, Ala., Amazon warehouse (failed) and the union vote at Starbucks in a large, northeastern city, Buffalo, N.Y. (successful). Workers at a Staten Island, N.Y., Amazon warehouse rejected unionization, which is not surprising because Republican Donald Trump trounced Joe Biden in the 2020 presidential election in the New York borough with more than 62% of the vote.

Gallup, in an article on its website, said, “Very similar to the recent data on the political orientation of union members, exit polls show that union households voted by a 17-percentage-point margin for Biden over Donald Trump in the 2020 presidential election.”

There is a deep indoctrination among conservatives that unions are tantamount to communism.

Data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics showed the percentage of workers repped by a union actually declined from 2020 to 2021 in Georgia from 6.5% to 5.8%. In 1999 9% of workers were unionized. But Georgia’s organized labor force is still not as meager as South Carolina, where 2% of wage and salary employees are represented by a union. Only six states had fewer workers repped by a union in 2021 than Georgia, and five of those states were in the South.

For decades Georgia was home to unionized auto plants where assembly line workers put together Fords and General Motors vehicles. The Ford plant closed in 2006 and General Motor’s Doraville Assembly shuttered soon after in 2008.

While they were open there was still enough union activity in Georgia that you might see unionized United Parcel Service drivers refuse to cross a picket line to deliver packages to the GM plant. Now, unions are far less visible save for the occasional airline pilot picket at the Atlanta airport.

Here is the biggest takeaway from Gallup analysis and whether unionization might creep into these right-to-work states all around us:

“Views of unions do not significantly divide the rich versus the poor, the highly educated versus the less well educated or women versus men. Views of unions are largely a factor of the individual’s underlying political and ideological orientation.”

It is not surprising then that the AFL-CIO of Georgia endorsed a Democrat, state Sen. Jen Jordan, in the upcoming election for Attorney General.

Beth Allen, a spokeswoman for CWA, said Apple “is running an anti-union campaign.” She said the company is holding “mandatory” meetings to tell workers why they should not join a union. These captive audience meetings are a violation of labor laws, according to a memo from Jennifer Abruzzo, the General Counsel of the National Labor Relations Board.

That’s where someone like Jordan, a Democrat, might step in as the state’s top cop and take a closer look at those mandatory meetings. Chris Carr, the incumbent she would challenge if he survives the May 24 GOP primary, would likely never do such a thing.

In addition, Biden is pushing the PRO Act, or Protecting the Right to Organize. The PRO Act would overturn the right to work laws in 27 states. Georgia’s U.S. Senators, Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock, support the PRO Act.

Conservatives insist a key reason companies, national and international, have been flocking to the South is right-to- work laws. Thomas J. Holmes of the University of Minnesota and Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis wrote a well-circulated paper in 1998 that found “there is a large, abrupt increase in manufacturing activity when one crosses a state border from an anti-business state (no right-to-work laws) into a pro-business state (right-to-work laws in place).

But that was in an era when manufacturing had a stronger foothold in the economy. Critics claim companies come to states like Georgia, Alabama, and South Carolina because of the huge tax incentives offered, not right-to-work laws.

And, according to The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, nine quality of life measures were used to rank the 50 states, and eight of the 10 worst states in terms of quality of life are Right to Work, while eight of the 10 best are not.

The tight labor market with unemployment at 3.6% (the lowest in 50 years except for two months) could help, but also hinder, unionization. Companies have had to increase pay and benefits to attract workers, which cuts into the need for a union, as some arguments go. At the same time, workers have emerging power and they are starting to voice concerns with their rising status.

Allen, the CWA spokeswoman, said Apple workers at Cumberland Mall are rallying to the union for issues related to the pall cast by the pandemic, more than for any other reason.

“Retail workers at Apple showed up, in person, during the pandemic, putting their health and well-being at risk,” Allen said in an email. “Meanwhile, corporate employees were able to work from home and have more of a voice in their overall working conditions.

“Workers want the kind of voice on the job and lasting changes to working conditions that they can achieve through joining together in a union and negotiating a collective bargaining agreement.”

According to the CWA, the union drive includes Apple salespeople, technicians, creatives, and operations specialists. By April 20th, 70% of the more than 100 eligible workers had signed union authorization cards.

Through the CWA media office, Derrick Bowles, Apple Genius worker and union member at Cumberland Mall said, “A number of us have been here for many years, and we don’t think you stick at a place unless you love it. Apple is a profoundly positive place to work, but we know that the company can better live up to their ideals and so we’re excited to be joining together with our coworkers to bring Apple to the negotiating table and make this an even better place to work.”

Less than a mile from the Apple store at Cumberland Mall, in the Atlanta Braves clubhouse at Truist Park, shortstop Dansby Swanson talked about what makes the Major League Baseball Players Association the strongest union in all of sports. A month after the players got back to work this spring after being locked out by owners, Swanson said the key to players union’s success is pouring opinions of 1,500 players down a funnel and one voice coming out the other end. It was multiple opinions for sure, he said, but one voice.

They were words of caution for the retail workers. Don’t cram opinions down one another’s throat to get traction toward a collective bargaining deal.

“Unanimous way of thinking is dangerous and I think that the more that you can piece together all these opinions and come out with one voice that’s more important than just having a unanimous consensus,” Swanson said. “I feel like there’s such a beauty and freedom of thought and expression in people and I feel like our union does such a good job of taking opinions of 1,500 guys, and being able to accumulate it into one voice. We all, at the end of the day, put our feelings aside and stand up for one another.”

In the end, however, a unified voice of a union may be no match for the unified opposition of conservative voters and the lawmakers they champion.

Georgia Recorder is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Georgia Recorder maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor John McCosh for questions: info@georgiarecorder.com. Follow Georgia Recorder on Facebook and Twitter.