by Robert C. Donnelly, Gonzaga University [This article first appeared in The Conversation, republished with permission]

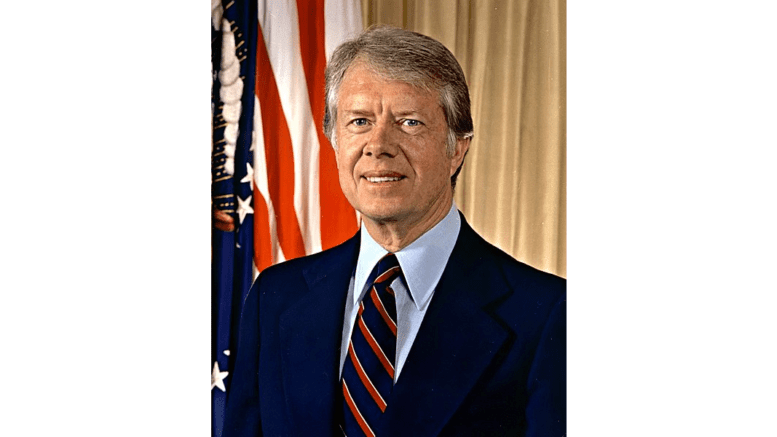

Former President Jimmy Carter, who has entered hospice care at age 98 at his home in Plains, Georgia, was a dark horse Democratic presidential candidate with little national recognition when he beat Republican incumbent Gerald Ford in 1976.

The introspective former peanut farmer pledged a new era of honesty and forthrightness at home and abroad, a promise that resonated with voters eager for change following the Watergate scandal and the Vietnam War.

His presidency, however, lasted only one term before Ronald Reagan defeated him. Since then, scholars have debated – and often maligned – Carter’s legacy, especially his foreign policy efforts that revolved around human rights.

Critics have described Carter’s foreign policies as “ineffectual” and “hopelessly muddled,” and their formulation demonstrated “weakness and indecision.”

As a historian researching Carter’s foreign policy initiatives, I conclude his overseas policies were far more effective than critics have claimed.

A Soviet strategy

The criticism of Carter’s foreign policies seems particularly mistaken when it comes to the Cold War, a period defined by decades of hostility, mutual distrust and arms buildup after World War II between the U.S. and Russia, then known as the Soviet Union or Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).

By the late 1970s, the Soviet Union’s economy and global influence were weakening. With the counsel of National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski, a Soviet expert, Carter exploited these weaknesses.

During his presidency, Carter insisted nations provide basic freedoms for their people – a moral weapon against which repressive leaders could not defend.

Carter soon openly criticized the Soviets for denying Russian Jews their basic civil rights, a violation of human rights protections outlined in the diplomatic agreement called the Helsinki Accords.

Carter’s team underscored these violations in arms control talks. The CIA flooded the USSR with books and articles to incite human rights activism. And Carter publicly supported Russian dissidents – including pro-democracy activist Andrei Sakharov – who were fighting an ideological war against socialist leaders.

Carter adviser Stuart Eizenstat argues that the administration attacked the Soviets “in their most vulnerable spot – mistreatment of their own citizens.”

This proved effective in sparking Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s social and political reforms of the late 1980s, best known by the Russian word “glasnost,” or “openness.”

The Afghan invasion

In December 1979, the Soviets invaded Afghanistan in response to the assassination of the Soviet-backed Afghan leader, Nur Mohammad Taraki. The invasion effectively ended an existing détente between the U.S. and USSR.

Beginning in July 1979, the U.S. was providing advice and nonlethal supplies to the mujahideen rebelling against the Soviet-backed regime. After the invasion, National Security Advisor Brzezinski advised Carter to respond aggressively to it. So the CIA and U.S. allies delivered weapons to the mujahideen, a program later expanded under Reagan.

Carter’s move effectively engaged the Soviets in a proxy war that began to bleed the Soviet Union.

By providing the rebels with modern weapons, the U.S. was “giving to the USSR its Vietnam war,” according to Brzezinski: a progressively expensive war, a strain on the socialist economy and an erosion of their authority abroad.

Carter also imposed an embargo on U.S. grain sales to the Soviets in 1980. Agriculture was the USSR’s greatest economic weakness since the 1960s. The country’s unfavorable weather and climate contributed to successive poor growing seasons, and their heavy industrial development left the agricultural sector underfunded.

Economist Elizabeth Clayton concluded in 1985 that Carter’s embargo was effective in exacerbating this weakness.

Census data compiled between 1959 and 1979 show that 54 million people were added to the Soviet population. Clayton estimates that 2 to 3 million more people were added in each subsequent year. The Soviets were overwhelmed by the population boom and struggled to feed their people.

At the same time, Clayton found that monthly wages increased, which led to an increased demand for meat. But by 1985, there was a meat shortage in the USSR. Why? Carter’s grain embargo, although ended by Reagan in 1981, had a lasting impact on livestock feed that resulted in Russian farmers decreasing livestock production.

The embargo also forced the Soviets to pay premium prices for grain from other countries, nearly 25 percent above market prices.

For years, Soviet leaders promised better diets and health, but now their people had less food. The embargo battered a weak socialist economy and created another layer of instability for the growing population.

The Olympic boycott

In 1980, Carter pushed further to punish the Soviets. He convinced the U.S. Olympic Committee to refrain from competing in the upcoming Moscow Olympics while the Soviets repressed their people and occupied Afghanistan.

Carter not only promoted a boycott, but he also embargoed U.S. technology and other goods needed to produce the Olympics. He also stopped NBC from paying the final US$20 million owed to the USSR to broadcast the Olympics. China, Germany, Canada and Japan – superpowers of sport – also participated in the boycott.

Historian Allen Guttmann said, “The USSR lost a significant amount of international legitimacy on the Olympic question.” Dissidents relayed to Carter that the boycott was another jab at Soviet leadership. And in America, public opinion supported Carter’s bold move – 73% of Americans favored the boycott.

The Carter doctrine

In his 1980 State of the Union address, Carter revealed an aggressive Cold War military plan. He declared a “Carter doctrine,” which said that the Soviets’ attempt to gain control of Afghanistan, and possibly the region, was regarded as a threat to U.S. interests. And Carter was prepared to meet the threat with “military force.”

Carter also announced in his speech a five-year spending initiative to modernize and strengthen the military because he recognized the post-Vietnam military cuts weakened the U.S. against the USSR.

Ronald Reagan argued during the 1980 presidential campaign that, “Jimmy Carter risks our national security – our credibility – and damages American purposes by sending timid and even contradictory signals to the Soviet Union.” Carter’s policy was based on “weakness and illusion” and should be replaced “with one founded on improved military strength,” Reagan criticized.

In 1985, however, President Reagan publicly acknowledged that his predecessor demonstrated great timing in modernizing and strengthening the nation’s forces, which further increased economic and diplomatic pressure on the Soviets.

Reagan admitted that he felt “very bad” for misstating Carter’s policies and record on defense.

Carter is most lauded today for his post-presidency activism, public service and defending human rights. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2002 for such efforts.

But that praise leaves out a significant portion of Carter’s presidential accomplishments. His foreign policy, emphasizing human rights, was a key instrument in dismantling the power of the Soviet Union.

This is an updated version of a story that was originally published on May 2, 2019.

Robert C. Donnelly, Associate Professor of History, Gonzaga University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.