By Ross Williams, Georgia Recorder [This article first appeared in the Georgia Recorder, republished with permission]

May 10, 2022

When Georgia college students return to their campuses in the fall, they could be in for more spirited intellectual debate than they’re used to.

The state Board of Regents, which oversees the state’s 26 public universities, voted Tuesday to change their institutions’ free speech policies to bring them in line with newly-signed state legislation.

The new policy largely does away with so-called campus free speech zones, areas of the campus open to protests and rallies. The zones are a relatively new concept in Georgia that has come under fire in recent years, especially with religious and conservative groups, who say the idea curtails First Amendment rights and opens the state up to lawsuits.

Last year, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of a former Georgia Gwinnett College student who was prevented from handing out religious literature on campus.

Under the change, set to go into effect July 1, members of the campus community — students, faculty, staff and invited guests — can have access to outdoor parts of campus for protests. Schools will have the ability to set certain restrictions such as disallowing late-night demonstrations outside a residence hall, but these restrictions cannot be based on the content of the speech.

People who are not part of the campus community can be restricted to specific high-traffic parts of the campus and made to comply with other restrictions, including the requirement to make reservations.

“Clearly, the Board of Regents is trying to thread the needle here with allowing free speech throughout the campus, without it being disruptive, and allowing people to make their case in a way that supports what all institutions of higher learning should support, which is free and open discussion of ideas,” said Richard T. Griffiths, president emeritus of the Georgia First Amendment Foundation.

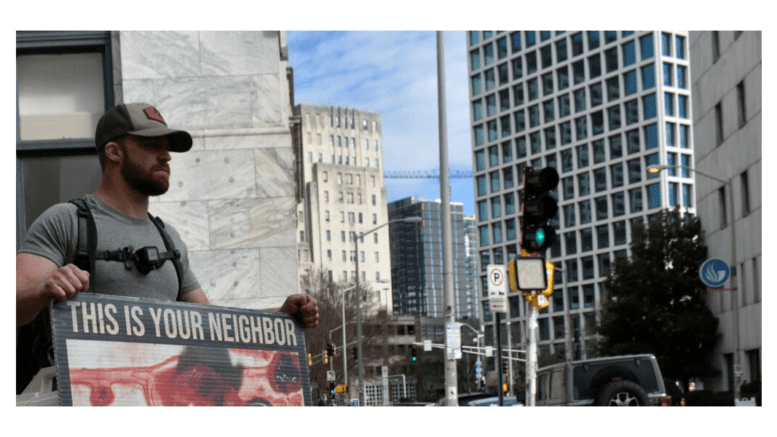

Others say some campus protests are less about the open exchange of ideas and more about threats and intimidation. While the idea was in the Legislature, critics expressed concern it could embolden fringe groups who go beyond distasteful speech to harrass students based on their race, religion or sexual orientation.

Georgia Tech student Alex Ames said she and classmates sometimes travel the campus in groups to protect each other from vitriolic protesters, who are particularly prone to shouting down Muslim, Jewish or LGBT students.

Ames said some of the distasteful demonstrations have been at the request of student groups, which means they could have free rein of campus in the future.

“Now there aren’t really places on campus where marginalized students can be safe from these extremist groups showing up,” Ames said. “And USG’s policy doesn’t just mean that students and faculty and staff can go on campus, it also means that outside, invited groups, like these extremist groups, you know, the ones that hold signs that say “Muslim people will go to hell,” or use slurs referring to LGBTQ students as they walk around, now, those groups could go across campus.”

Griffiths called the Regents’ plan to open campuses up to people who live or work there while maintaining restrictions on outsiders a nuanced and appropriate solution.

“Free speech is one of the great rights in our Constitution,” he said. “But as with all our great rights, we have to balance our rights against the rights of others, and it’s a beautiful thing when it works well, and a challenge when it doesn’t, but ultimately, it is free exchange of ideas in a setting that is respectful and open to dialogue that allows our society to move forward.”

For times when the dialogue is not open and respectful, college leaders need to make sure marginalized students who are being harassed have a way to report it and that administrators are able to respond — that only seems right when students are paying tens of thousands of dollars to attend classes, Ames said.

“It shouldn’t be on students to have to go out of their way to protest and keep each other safe when you’re paying tuition to be there,” she said. “And you should be able to walk across campus as a Muslim student or as a queer student without being harassed on your way to class. That’s the university’s responsibility to us.”

Georgia Recorder is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Georgia Recorder maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor John McCosh for questions: info@georgiarecorder.com. Follow Georgia Recorder on Facebook and Twitter.