by Madeline Steiner, University of South Carolina [This article first appeared in The Conversation, republished with permission]

The scary clown has become a horror staple.

Featuring Art the Clown as the main villain, Damien Leone’s new film “Terrifier 2” is so gruesome that there are reports of viewers vomiting and passing out in the theater. And every Halloween, you’ll see vicious clowns stalking haunted house attractions or trick-or-treaters dressed as Pennywise, the evil clown from Stephen King’s “It.”

It can be hard to imagine a time when clowns were regularly invited to children’s birthday parties and hospital wards – not to terrorize, but to delight and entertain. For much of the 20th century, this was the standard role of the clown.

However, clowns have always had a dark side. Before the 20th century, clowns in American circuses were largely considered a form of adult entertainment.

In my own research on the history of the 19th-century circus, I spend a lot of time in archives where I regularly come across vintage photos of clowns.

Now, I don’t consider myself afraid of clowns. In fact, I always try to remind folks that today’s clowns are serious artists with an enormous amount of training in their craft. But even I have to admit that the clowns I come across from old circuses give me the heebie-jeebies.

Drunken, lewd clowns in drag

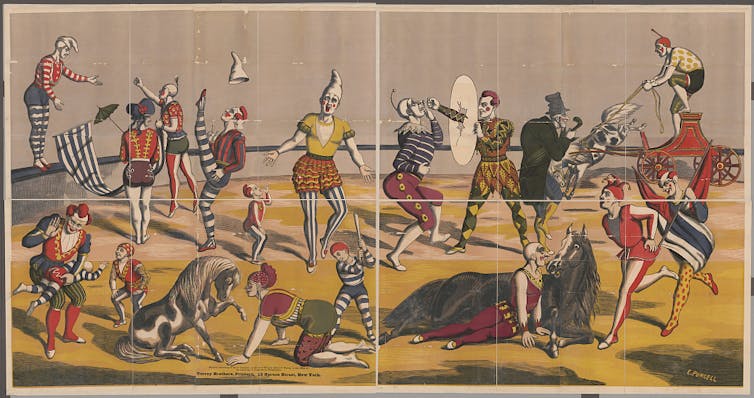

For most of the 19th century, circuses were relatively small, one-ring events where audiences could hear performers speak.

These shows were rowdy affairs in which audiences felt free to yell, boo and hiss at performers. Typically, clowns would engage in banter with the stoic ringmaster, who was often the target for the clowns’ pranks. Borrowing comedic traditions from the blackface minstrel show, circus clowns used puns, non sequiturs and exaggerated burlesque humor.

One very popular clown act, which Mark Twain depicted in “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” involved a performer disguised as a drunken circus patron who shocked the audience by entering the ring and clumsily attempting to ride one of the show’s horses before dramatically revealing himself to be part of the show. Famous 19th-century clown Dan Rice was known for including local gossip and political commentary in his performances and impersonating prominent figures in each town he visited.

The jokes they told were often misogynistic and full of sexual double-entendres, which wasn’t a problem because circus audiences at this time were mostly adult and male. Back then, circuses were a stigmatized form of entertainment in the U.S., considered disreputable for their association with gambling, grift, scantily clad female performers, profanity and alcohol. Church leaders regularly warned their congregations not to attend the circus. Some states even had laws banning circuses altogether.

Clowns played a part in the circus’ seedy reputation.

Showman P.T. Barnum noted that part of the appeal of the circuses “consisted of the clown’s vulgar jests, emphasized with still more vulgar and suggestive gestures.” Clowns also subverted gender norms, with many appearing in drag, often exaggerating the female figure with cartoonishly big fake breasts.

In the early 19th century, some circuses also featured a separate tent that contained a “cooch show.” Male patrons were invited, for a fee, to watch women dance and strip.

Circus historian Janet Davis notes that some of these performances included clowns in drag “playing gender-bending pranks on dumbfounded men who expected to see nude women.” In a shocking revelation, Davis also notes that at some cooch show performances, gay clowns had sexual encounters with male audience members “during and after anonymously crowded scenes.”

These clowns, suffice it to say, weren’t for kids.

Clowns clean up their act

It wasn’t really until the 1880s and 1890s, when entertainment impresarios like Barnum made efforts to “clean up” the circus to draw in a larger audience, that clowns truly became associated with children.

After circuses started traveling by railroad, they could carry more equipment, allowing them to expand from one ring to three. Audiences could no longer hear performers, so the clown became a pantomime comedian, eliminating any potentially vulgar or suggestive language.

Circus owners, aiming to make as much money as possible, tried to court a broader audience, including women and children. That necessitated the removal of any scandalous acts and strict monitoring of their employees’ behavior.

The shows with the most staying power, like Barnum & Bailey’s Greatest Show on Earth, were known as “Sunday school” shows, free of any objectionable content. They successfully portrayed themselves as the purveyors of good, clean fun.

Clowns played a role in this transformation. With now-silent acts focused on physical comedy, their performances were easy for children to understand. Clowns remained tricksters, but their slapstick comedy was seen as all in good fun.

This had a lasting effect. Clowns entertained families at the circus, and, as entertainment moved to film and television, child-friendly clowns followed there too. Clowns became staples of children’s entertainment in the 20th century. A popular television program featuring Bozo the Clown ran for 40 years, from 1960 to 2001. Beginning in the 1980s, clowns became regular visitors to children’s hospitals to cheer up young patients. And companies like McDonald’s used clowns as mascots to make their brands appealing to children.

But in the 21st century, there’s been a sharp turnaround. A 2008 study concluded that “clowns are universally disliked” by children today. Some point to clown-turned-serial killer John Wayne Gacy as the turning point, while others may blame Stephen King’s “It” for yoking clowns to horror.

Upon examining the history of the American circus, it almost seems as if the period in the 20th century when clowns were beloved by children deviated from the norm. Today’s scary clowns are not a divergence from tradition, but a return to it.

Madeline Steiner, Postdoctoral Fellow of History, University of South Carolina

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.