by Jane E. Kirtley, University of Minnesota, [This article first appeared in The Conversation, republished with permission]

Can Americans be jailed for making fun of the government? Most would respond with a resounding “No, of course not! The First Amendment protects us from that.”

But Anthony Novak learned otherwise in March 2016, after he created and posted a fake version of the Parma, Ohio, Police Department’s Facebook page.

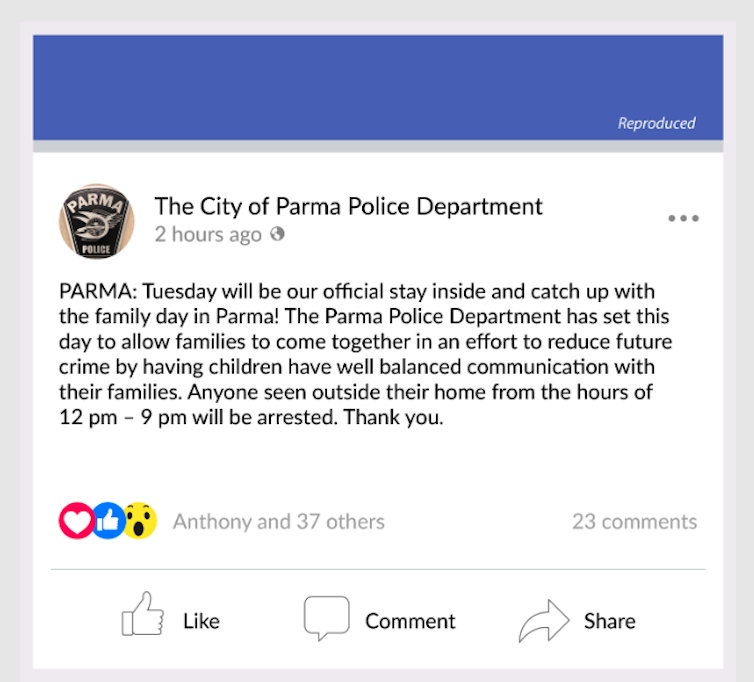

He copied the department’s name and profile picture onto his satirical Facebook page, but unlike the official page, Novak’s was designated a “Community” page and displayed the slogan: “We no crime,” a parody of the department’s actual slogan, “We know crime.”

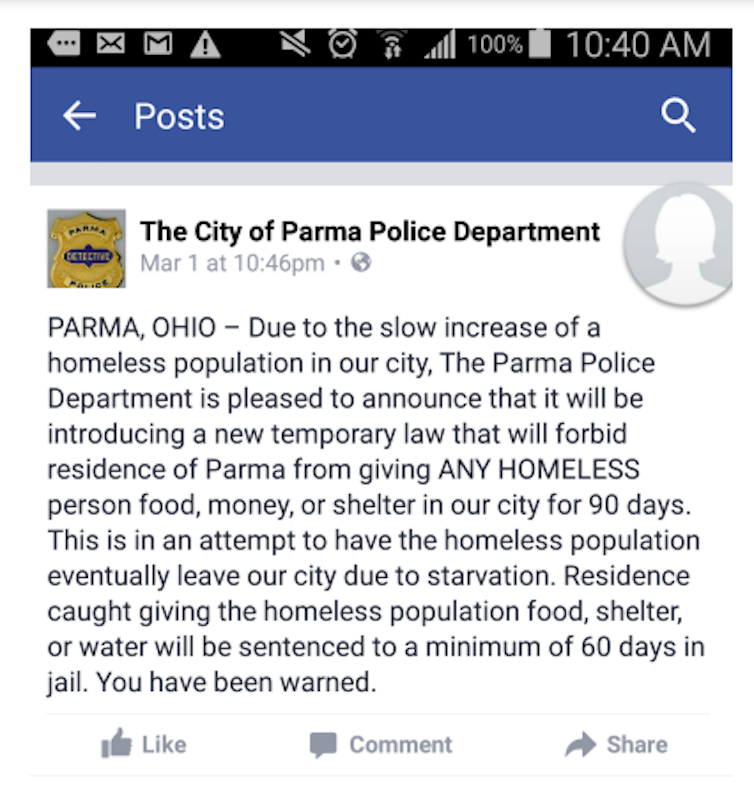

During its short life – the page was available for only about 12 hours – Novak published six posts, all parodies. One – echoing Jonathan Swift’s classic satire, “A Modest Proposal,” that suggested Ireland’s poor sell their children as food for the rich – announced a new law forbidding residents to give “ANY HOMELESS person food, money, or shelter in our city for 90 days,” so that “the homeless population eventually leave our city due to starvation.”

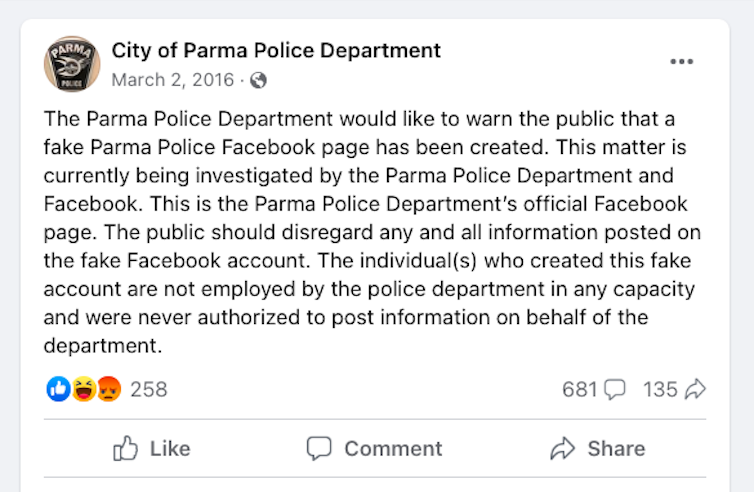

Parma police promptly posted a notice on its official page, warning residents not to be fooled by Novak’s parody. Novak in turn posted that same notice on his own page, but also deleted the few posted reader comments opining that his page was fake. After police announced a criminal investigation, Novak took his page down entirely.

Novak asked the U.S. Supreme Court to rule in the resulting court case stemming from the police’s heavy-handed treatment of him. In late February 2023, the high court refused to take the case, forfeiting an opportunity to make a definitive statement about how far free speech protections extend when it comes to satire about government.

A screenshot from Anthony Novak’s fake Parma Police Department Facebook page. City of Parma brief to U.S. Supreme Court

First Amendment protection?

Here’s how the case developed: Citing a state law making it a crime to use a computer to disrupt police operations, the police searched Novak’s apartment, seized his phone and laptop and jailed him for four days. A jury acquitted him of the felony charge in August 2016.

Novak then filed a lawsuit against the police, arguing that they had violated his First Amendment rights.

The law enforcement officials replied that they were entitled to “qualified immunity,” a legal doctrine protecting government employees from liability for conduct that has not been clearly established as unconstitutional.

A three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit, which has jurisdiction over cases from Ohio, Kentucky, Michigan and Tennessee, ruled that although parody is protected speech, copying the department’s official warning and deleting the comments questioning the page’s authenticity might not be. It concluded that the officers could have reasonably believed that some of Novak’s Facebook activity violated the criminal statute and was not protected by the First Amendment.

Novak asked the Supreme Court to review his case in September 2022. He argued that police should not be allowed to arrest an individual solely for making fun of the government, yet “that is exactly what happened here. If that is not an obvious violation of the Constitution, it’s hard to imagine what would be.” Novak also invited the high court to reconsider the qualified immunity doctrine, especially in cases where protected speech is the basis for arresting someone.

The police response solemnly predicted that a ruling in Novak’s favor could lead to a virtual law enforcement Armageddon, confusing the public, eroding their trust in official social media sites, posing a threat to safety and “exacerbate[ing] the nationwide crisis police agencies are experiencing.”

Parma’s police department posted on its legitimate Facebook page a warning about the satirical page. City of Parma Police Department Facebook page

The Onion weighs in

Novak’s petition was supported by amicus curiae briefs by politically diverse “friends of the court,” including the satirical news sites The Onion and The Babylon Bee, who argued that their own survival depends on First Amendment protection for parody.

Acknowledging that its own writing has occasionally confused some readers, The Onion pointed out that satire only works if it credibly mimics whatever it is parodying. The courts, they wrote, should not assume “that ordinary readers are less sophisticated and more humorless than they actually are.”

The Onion concluded by declaring it “intends to continue its socially valuable role bringing the disinfectant of sunlight into the halls of power. And it would vastly prefer that sunlight not to be measured out to its writers in 15-minute increments in an exercise yard.”

But on Feb. 21, 2023, the Supreme Court chose to deny the petition for certiorari. The court would not hear the case.

Coincidentally, this order was issued three days before the 35th anniversary of the release of the Supreme Court’s opinion in Hustler Magazine, Inc. v. Falwell. That major ruling established that the legal tradition protecting robust criticism of public figures and government operations must extend to satirical cartoons and parody, however “caustic” they may be.

From the 19th century caricaturist and editorial cartoonist Thomas Nast to the creators of the animated “South Park” TV show and movie, satirists do their best work when they are free to skewer public officials and celebrities without fear of legal consequences.

And as then-Chief Justice William Rehnquist, the author of the Hustler opinion and himself a one-time editorial cartoonist, wrote for the unanimous court, “From the viewpoint of history, it is clear that our political discourse would have been considerably poorer without them.”

One of the Facebook parody pages made by Anthony Novak, satirizing the Parma Police Department in Ohio. Institute for Justice, CC BY-SA

Violating American tradition

The Hustler case, however, was a civil action for emotional distress filed by the Rev. Jerry Falwell after the magazine published an “ad parody” making fun of the nationally known fundamentalist minister.

By contrast, Novak was arrested, detained and criminally prosecuted for lampooning the police, who were seeking to deprive him of his liberty and, presumably, serve as a warning to others.

Using criminal statutes to silence satirists and parodists occurs in countries like Russia, Iran and Thailand, where officials tolerate no disrespect. I believe that it is distinctly un-American.

Yet as recently as 2010, Justice Neil Gorsuch, then a judge for the 10th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals, wrote that “the Supreme Court has yet to address how far the First Amendment goes in protecting parody.” That was in a case challenging a prosecutor’s claim of qualified immunity after she approved the search, seizure and arrest of a parodist for allegedly violating the Colorado criminal libel statute.

Refusing to review Novak’s case is a missed opportunity for the Court to consider and decide once and for all whether the First Amendment protects satire and parody. And that’s no joke.

Jane E. Kirtley, Professor of Media Ethics and Law, University of Minnesota

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.