by Melanie Dallas, LPC

If you were to come to Highland Rivers Behavioral Health for services, one of the first documents you’d be given is a list of your rights as an individual receiving treatment from our agency. Among these are the right to confidentiality, to access your own records, to informed consent about your treatment, and to file a grievance. The document is an acknowledgement that your rights as an individual don’t stop simply because you may be struggling with mental illness.

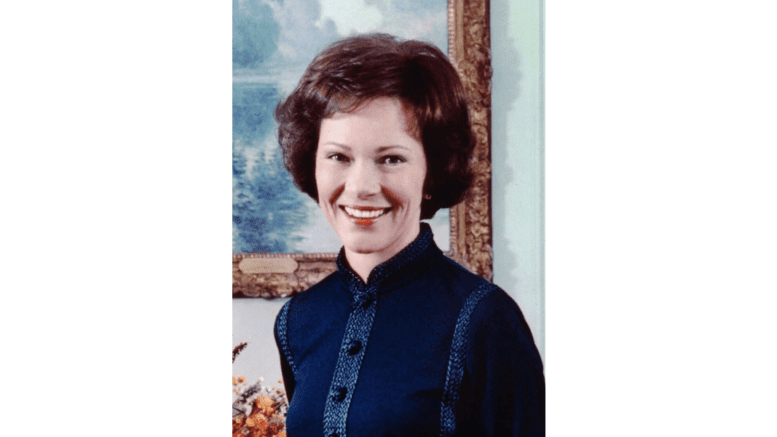

What you may not realize is that list of patient rights is a legacy of the work of former First Lady Rosalynn Carter, who passed away November 19. It is but one of many ways her impassioned work impacted our collective understanding of mental illness and how mental health services are delivered to individuals.

Although Rosalynn Carter may have seemed to many the epitome of genteel Southern grace, she was also known to be smart, shrewd and assertive. Nor was she afraid to ask tough – and insightful – questions. One of the best was this: How much of the chronicity that we see in mental illness is due to the illness, and how much is due to the way that society and the mental health professionals treat people with severe mental illnesses? Answering that question, and changing that equation, was her life’s work.

While in the White House, Mrs. Carter was appointed by her husband President Jimmy Carter as honorary chair of the Presidential Commission on Mental Health, an initiative largely undertaken at Mrs. Carter’s urging. The resulting legislation, the Mental Health Systems Act in 1980, was the first federal work on the nation’s mental health system in nearly two decades. Although many of the law’s provisions were repealed by the subsequent administration, Section 501 – “Bill of Rights” – was not, and has remained the foundation for patients’ rights in mental health treatment ever since.

Returning to Georgia in 1981, Mrs. Carter continued this work with perhaps even more fervor. When she and the former President founded the Carter Center the next year, mental health was at the forefront of its mission. Reviewing the list of center’s annual mental health programs shows what pioneering work was done there, with programs as far back as the 1990s on children’s mental health, access to care, racial disparities, and the connection between physical and mental health – topics all considered fundamental to the mental health field today. Indeed, the Carter Center held its first program about recovery – today the very core of mental health treatment – in 1999!

Judy Fitzgerald, former commissioner of the Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities, began her career at the Carter Center, where she had the privilege of working with Rosalynn Carter personally; she was kind enough to share her thoughts about Mrs. Carter with me:

“It is a testament to former First Lady Rosalynn Carter’s remarkable legacy that issues that were top of her mind several decades ago, like mental health parity and caregiving, are now at the forefront of our national conversation. She was intelligent, compassionate and persistent, and a person that others trusted with their stories, their hopes and their dreams. She was a person of grace, wisdom, and fortitude who shared these gifts generously with the world…and we are better for it.”

As for Mrs. Carter herself, I saw a quote from her autobiography that I think not only illuminates her humane approach to her life’s work, but also the compassion that drove it:

“I wanted to take mental illnesses and emotional disorders out of the closet, to let people know it is all right to admit having a problem without the fear of being called crazy. If only we could consider mental illnesses as straightforwardly as we do physical illnesses, those affected could seek help and be treated in an open and effective way.”

That we in the mental health field work daily to do just that is perhaps Rosalynn Carter’s greatest legacy.

Melanie Dallas is a licensed professional counselor and CEO of Highland Rivers Behavioral Health, which provides treatment and recovery services for individuals with mental illness, substance use disorders, and intellectual and developmental disabilities in a 13-county region of northwest Georgia that includes Bartow, Cherokee, Cobb, Floyd, Fannin, Gilmer, Gordon, Haralson, Murray, Paulding, Pickens, Polk and Whitfield counties.