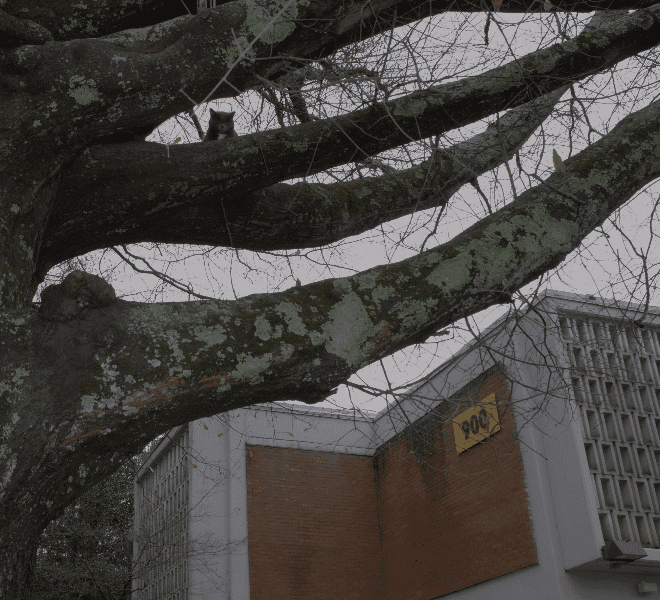

A feral cat in a tree in Marietta on January 26, 2024: Photo by Jason Fussell

by Jason Fussell

MARIETTA, Ga. — A cat popped its head out from a decorative wall with a look of intrigue and caution before retreating behind the wall and popping out once more. With a final retreat, the animal sauntered down the steps into a staff parking lot, where it began inspecting the cars therein.

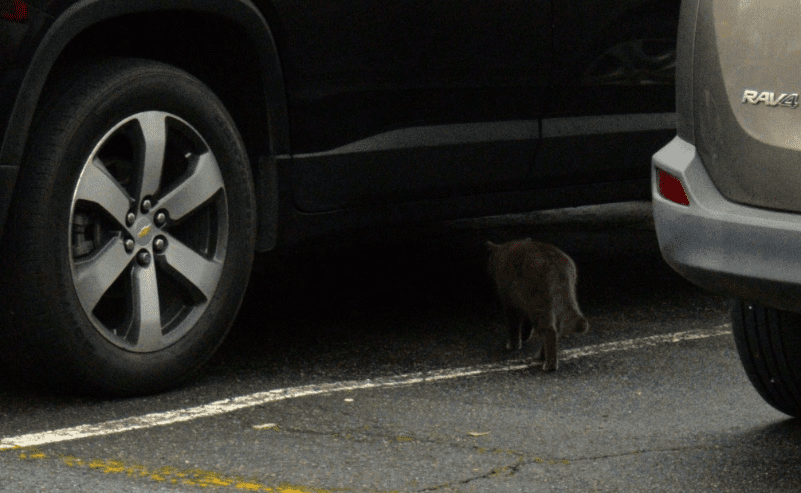

While searching for a place to hide, the cat’s clipped ear twitched at the sounds of scurrying birds and squirrels before it propped itself up to peer into the undercarriage of one of the cars. This would have been his hiding spot since it was relatively warm compared to the frigid temperatures in the morning of January 26, but the morning’s rain made the car an unsuitable candidate.

Instead, the cat scurried away, under a maintenance cart, and up the branches of a nearby tree, nearly blending into its surroundings as it curled up for an hour-long nap. The cat ignored the sounds of critters above while it slept, and passersby would not have known he was there.

The cat underneath a car in the parking lot on campus. Marietta, Ga. on Jan. 26th, 2024. Photo by Jason Fussell.

This cat, who lives on the Marietta campus of Kennesaw State University, is merely one of a vast number of feral strays who call not just Cobb County, but most of the United States its home. Over the last three weeks, outdoor cats, including feral cats like this one as well as domestic cats that live outside, have been subject to the freezing cold temperatures in the area, with some lows reaching 11 degrees or lower.

Aside from the sheer danger that freezing temperatures can impose on the biological systems of outdoor domestic cats, there are other physical dangers that leave them vulnerable to injury, infection and even death.

The cat in its tree next to building 900 of the KSU Marietta campus. Marietta, Ga. on Jan. 26th, 2024. Photo by Jason Fussell.

“A lot of times when it’s really cold, they try to find places to get to warmth,” said Rachel Keith, a veterinary technician for Kennesaw Mountain Animal Hospital. “Cats can climb into car engines. They can go near HVAC systems. That can be dangerous, and that could cause extremities or tail injuries.”

These cats rarely, if ever, have access to the care they might need, and usually can only rely on their instincts to remedy their injuries. Too far from their homes, or maybe even lacking a home to begin with, cats like the ones on campus may not survive even the slightest damage.

“With injuries like that, like let’s say they get their tail caught in some sort of fan system to get to a heat source,” Keith said. “They can try to fix it themselves, clean it themselves and maybe chew at it themselves, which is a natural instinct, but that can cause a lot more serious issues that may lead, ultimately, to death if it gets too infected.”

With many outdoor cats, there is a sense of community responsibility that stems from the affection many of their neighbors hold, viewing them as a community pet. Patrick Miller, 56, lives in one such neighborhood where feral, unowned and free-ranging cats are abundant.

“We do give them names,” Miller said. “There was an old, gnarly, grizzled cat, we called him or her ‘warrior” based on the series of books Lily [his daughter] read. We have several names for the different cats we see.”

The cats in Miller’s neighborhood have sometimes been treated as a part of the families who live there, with some of them being fed and cared for by those living there.

“We have a large bag of dry cat food which we keep in the garage, and on multiple occasions I have caught one of the strays inside our garage trying to get the food,” Miller said. “I love cats, so I like them, although I do worry about them out in the elements.”

How can neighborhoods like Miller’s protect the cats they see around their homes? The answer is not as simple as feeding or sheltering and involves a more proactive approach on the part of cat owners.

“In my opinion as a wildlife biologist, domestic cats should be kept inside,” said Nicholas Green, assistant professor of biology at Kennesaw State University, who received a doctorate in biology from Baylor University in 2012. “…because of the risk that they could go hunting by themselves or just escape and become feral.

“You know the old Bob Barker line he closed The Price is Right with, ‘Spay and neuter your pets?’” Green said. “Part of the reason for that is to prevent escaped pets from becoming part of a feral breeding population. So, spaying and neutering your pets at home is a good first step. Not letting them escape and become feral is the next best step.”

The reason for Green’s advocacy for this proactive measure is that feral cats are seen as an invasive species by organizations such as the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which estimated in 2021 that there were between 30 and 80 million unowned or feral cats across the country. Their status as an invasive species was determined by their harmful impact on the animal species and habitats in their respective environments, according to the USDA.

“The modern domestic cat originated in the Near East,” Green said. “They are invasive in North America by any reasonable sense. They came over with European settlers during that time period. There are native wildcats in North America, but those native wildcats are not as prolific. They don’t reproduce as quickly as modern domestic cats.”

Measures like keeping pet cats inside and spaying or neutering them not only help to prevent additional stray or feral cats being added to the population, but they also prevent the injuries related to cold weather that can affect any cat, feral or not. How should communities handle the feral cats that are already present?

“There are a lot of rescue organizations,” Keith said. “Sometimes they can either provide you with…it’s like a trap, and it’s not painful at all. It’s just a kind of a metal cage and you can put food inside, and once they go in, it shuts and locks the animal in there. Of course, you need to make sure you’re monitoring that, and then get the cat…and then you can take that to that rescue organization.”

Fully feral cats typically want nothing to do with people, and may pose a physical threat if cornered, especially when injured. Keith said it is recommended that one should seek assistance from professionals in their area if they are not comfortable capturing the animal on their own.

As a last resort, communities can invest in artificial habitats or shelters for the animals; however, this action does come with its own potential risks.

“You might get something else, like rats or an opossum,” Green said. “That’s always a possibility with putting artificial habitats out in the world, right? You don’t know what’s going to move in.”

For those willing to take the risk to provide alternative areas for local cats to shelter, the availability of such products ranges from pre-built structures to simple additions that anyone could make.

The cat eating from his bowl full of dry food. Marietta, Ga. on Jan. 26th, 2024. Photo by Jason Fussell.

“There are awesome, on Amazon, ‘cat houses.’ Some are heated, even, that you can plug in,” Keith said. “But, even a cardboard box with a hole in it…and water and food, so that instead of going to more dangerous areas, they’ve got a safe shelter that you could provide.”

These kinds of provisions are what help the campus cat stay safe in the event of freezing conditions. After its nap, the cat climbed down and jaunted back to the wall, where it ate from one of the many bowls of food that students and/or faculty left out.

Once it had its fill, it continued its patrol up the sidewalk and along a wall over the building’s HVAC system. It watched for a moment as students walked by, then it walked back to the parking lot, where it lunged at a squirrel before sauntering away to continue its day of fending for itself, without a home to keep it safe or to keep its habitat safe from his predatory instincts.

The cat walking away under a car. Marietta, Ga. on Jan. 26th, 2024. Photo by Jason Fussell.

Jason Fussell is a student at Kennesaw State University studying Journalism and Emerging Media. As a journalist, Jason focuses on local stories about community events and festivals. He will graduate in May and plans to pursue a career in journalism after graduation.