by Alex Hinton, Rutgers University – Newark, [This article first appeared in The Conversation, republished with permission]

“No profanity.”

This is the one rule spelled out on a sign in Lance Walker’s barbershop in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, where political discussion between clients can get heated.

Three weeks before the election, on Oct. 14, 2024, I watched as Walker interviewed Michele Jansen, a conservative local talk show host, and Don Marritz, a liberal legal aid attorney also living in Pennsylvania, in his podcast studio.

Jansen and Marritz discussed the difficulties they had faced in the preceding months as they struggled to draft a document called Declaration Rejecting Political Violence. Eventually, more than 250 community leaders and citizens in Franklin and Adams counties in Pennsylvania signed on.

This effort – part of a project focused on preventing political violence run by the nonprofit group Urban Rural Action, or UR Action – almost fell apart over an argument over including the word “insurrection.”

Indeed, words have become contentious on the American political landscape. They turn dinner conversations into battlefields. And they provide politicians with fuel to stoke the flames of polarization.

An anthropologist, I have long studied international political violence and its prevention. More recently, I have done related research in the U.S. that resulted in a 2021 book, “It Can Happen Here.”

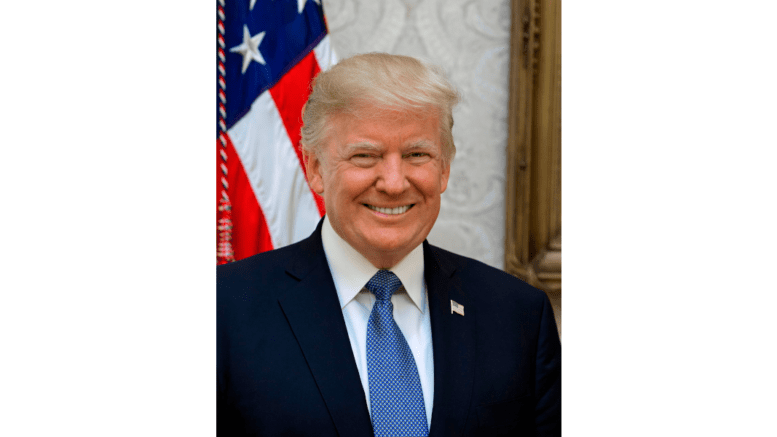

Now I’m studying toxic polarization in the U.S. and ways to reduce it. I have attended Make America Great Again events and spoken to voters who supported Kamala Harris or Donald Trump.

I have also observed the work of groups such as UR Action that try to bridge political divides.

During this research, I have found that some words are often understood differently by those on opposite sides of the political aisle. As a result, misunderstandings create tension and sometimes provoke anger.

Becoming aware of how and why certain words upset those with different political views, then, is a key step in reducing polarization. Here are five that can trigger Trump supporters and further isolate them from liberal Americans.

‘Incitement’ and ‘insurrection’

The suggestion that Trump incited an insurrection on Jan. 6, 2021, at the U.S. Capitol sparked the fight over the wording of the political violence denunciation.

Jansen later explained to me that she was concerned about widespread accusations that Trump incited violence at the U.S. Capitol – and that, more broadly, “people on the right are more targeted as hateful and using hate speech.”

Chad Collie, another conservative member of the UR Action declaration team, told me in an interview that Trump supporters “take offense” when the terms “incitement” and “insurrection” are used to describe Trump’s Jan. 6 rally. In their view, he added, Trump’s rally near the White House was a largely peaceful “protest” hijacked by a small number of violent people who stormed the Capitol.

More broadly, many Trump voters believe that the president-elect is the victim of “lawfare,” meaning efforts to unjustly use laws to attack political opponents.

As evidence, some Trump supporters point to the defeat of both of his impeachments and various criminal court cases brought against Trump, most of which have been paused or dismissed after he won the 2024 election.

Wokeness triggers like ‘they-them’ and ‘equity’

“Kamala is for they/them. President Trump is for you.”

Attack ads that feature phrases like this don’t necessarily win elections.

But gender identity was a nonstop talking point at the dozen or so MAGA events I attended ahead of the election. Speakers there constantly mocked the use of nonbinary pronouns and blasted the “radical left” for “transgender insanity.” This “insanity,” in their view, includes issues such as transgender people using bathrooms that match their gender identity and participating in sports competitions.

The word “equity” – along with related terms such as “diversity,” “critical race theory,” “social justice,” “privilege” and “DEI,” short for “diversity, equity and inclusion” – can also anger a Trump supporter.

They associate these words with a “woke” or even “communist” agenda that they think the “radical left” is trying to impose on them.

While some people think that these terms speak to efforts to recognize that groups of marginalized people, including people of color and women, have long faced discrimination, many Trump supporters think that related “woke” policies threaten their free speech and individual and family rights.

‘Racist’

Trump supporters were called “deplorables” by former presidential candidate Hillary Clinton in 2016.

But my interviews and observations show that no word, not even “fascist,” stings Trump supporters as much as being called a “racist,” an accusation that is widely used against them.

As Matt Schlapp, the head of the conservative group Conservative Political Action Committee, which runs the annual CPAC conference, laments in a book, “There is no way to escape its putrid stink.” The “racist” label, Schlapp explains from experience, shames, stigmatizes and makes a person afraid to speak.

More broadly, the use of “racist” and related terms plays into many Trump voters’ perceptions and anger that Democrats are elitist liberals who they think look down upon and even hate them.

Trump and Republican influencers frequently play on this resentment. Trump, for example, wore an orange and yellow safety vest as he sat in a garbage truck after Biden referred to them as “garbage.” Trump’s supporters soon started wearing vests and even garbage bags to his preelection events to show their support for Trump.

No one, however, wore a shirt to a Trump rally emblazoned with the word “racist.”

Words are like bees

America’s political division is intertwined with how language – sometimes a single word – can be understood differently by liberals and conservatives and trigger a negative reaction.

This reality has policy implications.

For example, when Philanthropy for Active Civic Engagement, an organization seeking to enhance civic and democratic life, examined perceptions of civic terms starting in 2019, they found that using certain works such as “equity” is often perceived as “liberal and college educated.” Their survey found that conservatives view terms such as “diversity,” “social justice,” “racial equity” and “activism” much more negatively than liberals.

These findings have led organizations that try to decrease political polarization in the U.S. to modify their messaging and more often use terms such as “unity,” “citizens” and “liberty,” which the civics language study found appeals to both liberals and conservatives.

Words don’t just provoke, then. They can also provide a path forward.

As the saying goes, “Words are like bees; some create honey, but others leave a sting.”

Alex Hinton, Distinguished Professor of Anthropology; Director, Center for the Study of Genocide and Human Rights, Rutgers University – Newark

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.