By Thomas Adam, University of Arkansas [This article first appeared in The Conversation. Used with permission]

Each season, the celebration of Christmas has religious leaders and conservatives publicly complaining about the commercialization of the holiday and the growing lack of Christian sentiment. Many people seem to believe that there was once a way to celebrate the birth of Christ in a more spiritual way.

Such perceptions about Christmas celebrations have, however, little basis in history. As a scholar of transnational and global history, I have studied the emergence of Christmas celebrations in German towns around 1800 and the global spread of this holiday ritual.

While Europeans participated in church services and religious ceremonies to celebrate the birth of Jesus for centuries, they did not commemorate it as we do today. Christmas trees and gift-giving on Dec. 24 in Germany did not spread to other European Christian cultures until the end of the 18th century and did not come to North America until the 1830s.

Charles Haswell, an engineer and chronicler of everyday life in New York City, wrote in his “Reminiscences of an Octoganarian” that in the 1830s German families living in Brooklyn dressed up Christmas trees with lights and ornaments. Haswell was so curious about this novel custom that he went to Brooklyn in a very stormy and wet night just to see these Christmas trees through the windows of private homes.

The first Christmas trees in Germany

Only in the late 1790s did the new custom of putting up a Christmas tree decorated with wax candles and ornaments and exchanging gifts emerge in Germany. This new holiday practice was completely outside and independent of Christian religious practices.

The idea of putting wax candles on an evergreen was inspired by the pagan tradition of celebrating the winter solstice with bonfires on Dec. 21. These bonfires on the darkest day of the year were intended to recall the sun and show her the way home. The lit Christmas tree was essentially a domesticated version of these bonfires.

The English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge gave the very first description of a decorated Christmas tree in a German household when he reported in 1799 about having seen such a tree in a private home in Ratzeburg in northwestern Germany. In 1816 German poet E.T.A. Hoffmann published his famous story “Nutcracker and Mouse King.” This story contains the very first literary record of a Christmas tree decorated with apples, sweets and lights.

From the onset, all family members, including children, were expected to participate in the gift-giving. Gifts were not brought by a mystical figure, but openly exchanged among family members – symbolizing the new middle-class culture of egalitarianism.

From German roots to American soil

American visitors to Germany in the first half of the 19th century realized the potential of this celebration for nation building. In 1835 Harvard professor George Ticknor was the first American to observe and participate in this type of Christmas celebration and to praise its usefulness for creating a national culture. That year, Ticknor and his 12-year-old daughter Anna joined the family of Count von Ungern-Sternberg in Dresden for a memorable Christmas celebration.

Other American visitors to Germany – such as Charles Loring Brace, who witnessed a Christmas celebration in Berlin nearly 20 years later – considered it a specific German festival with the potential to pull people together.

For both Ticknor and Brace, this holiday tradition provided the emotional glue that could bring families and members of a nation together. In 1843 Ticknor invited several prominent friends to join him in a Christmas celebration with a Christmas tree and gift-giving in his Boston home.

Ticknor’s holiday party was not the first Christmas celebration in the United States that featured a Christmas tree. German-American families had brought the custom with them and put up Christmas trees before. However, it was Ticknor’s social influence that secured the spread and social acceptance of the alien custom to put up a Christmas tree and to exchange gifts in American society.

The introduction of Santa Claus

For most of the 19th century, the celebration of Christmas with Christmas trees and gift-giving remained a marginal phenomenon in American society. Most Americans remained skeptical about this new custom. Some felt that they had to choose between older English customs such as hanging stockings for presents on the fireplace and the Christmas tree as proper space for the placing of gifts. It was also hard to find the necessary ingredients for this German custom. Christmas tree farms had first to be created. And ornaments needed to be produced.

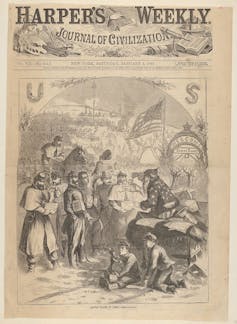

The most significant steps toward integrating Christmas into popular American culture came in the context of the American Civil War. In January 1863 Harper’s Weekly published on its front page the image of Santa Claus visiting the Union Army in 1862. This image, which was produced by the German-American cartoonist Thomas Nast, represents the very first image of Santa Claus.

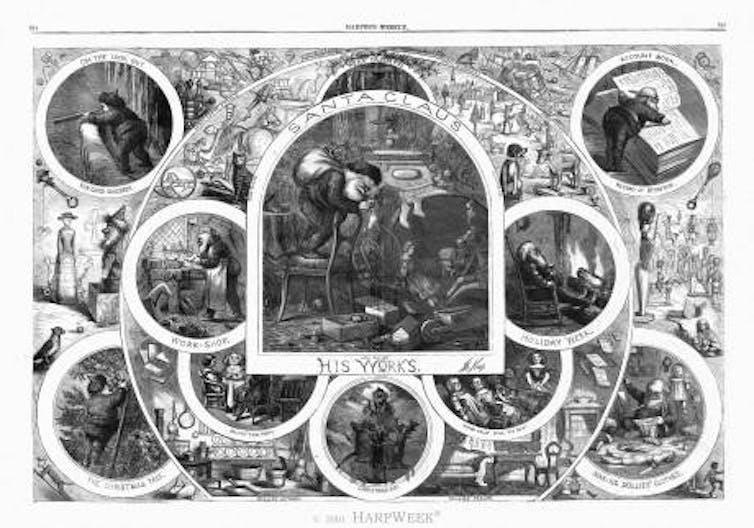

In the following years, Nast developed the image of Santa Claus into the jolly old man with a big belly and long white beard as we know it today. In 1866 Nast produced “Santa Claus and His Works,” an elaborate drawing of Santa Claus’ tasks, from making gifts to recording children’s behavior. This sketch also introduced the idea that Santa Claus traveled by a sledge drawn by reindeer.

Declaring Christmas a federal holiday and putting up the first Christmas tree in the White House marked the final steps in making Christmas an American holiday. On June 28, 1870, Congress passed the law that turned Christmas Day, New Year’s Day, Independence Day, and Thanksgiving Day into holidays for federal employees.

[Over 140,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletters to understand the world. Sign up today.]

And in December 1889 President Benjamin Harrison began the tradition of setting up a Christmas tree at the White House.

Christmas had finally become an American holiday tradition.

Thomas Adam, Associate Professor of International and Global Studies, University of Arkansas

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.