by Ross Williams, Georgia Recorder [This article first appeared in the Georgia Recorder, republished with permission]

May 26, 2022

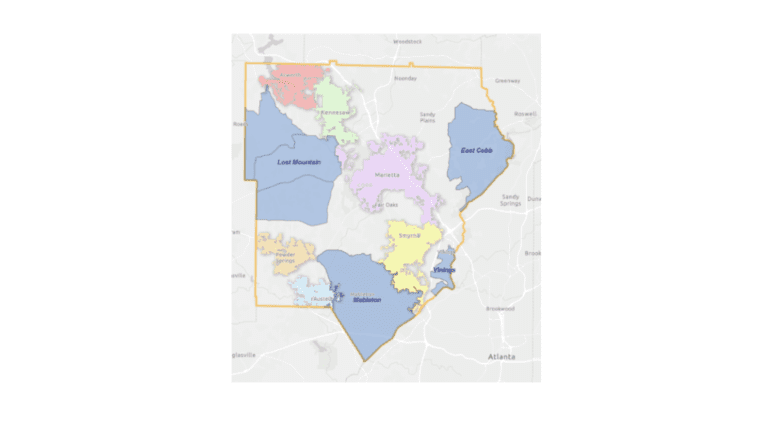

Efforts to carve three new cities out of Cobb County failed Tuesday night after voters shot down ballot measures in the eastern, western and southern portions of the suburban Atlanta county.

The proposed city of East Cobb failed by the largest margin with 5,900 in favor, good for 26.6% of the vote to 16,289 opposed, or 73.4%. Lost Mountain in west Cobb failed 42% to 58% with the anti side up over 4,000 votes, and Vinings in the south came closest to passing at 55% to 45%, decided by 255 votes out of 2,555.

“I think it was the right vote,” said Marietta state Rep. Don Parsons, the sole Cobb Republican who voted against the legislation in the House that put the referendum on the primary ballot. “I think it was the correct vote on part of people within the proposed city limits to vote it down.”

Parsons does not live within the proposed city limits, so the question did not appear on his ballot and he did not campaign against it, but parts of his district were within one version of the boundaries and bordering others.

In a floor speech during the 2022 legislative session, Parsons questioned whether the proposed area was cohesive enough to make up its own city as well as whether the public support was there to do so.

“On the floor, I said, at that time, I had not received one call or one piece of correspondence, email, telephone call, a letter, anything in favor of it, and that was the truth,” he said Wednesday. “After that vote, I got two emails wanting to know why I was opposed to it and upset that I had taken the floor to speak against it. And to this day, those are the only two emails or any kind of correspondence I’ve ever gotten in favor. It was overwhelmingly, all along, correspondence and emails opposed to it.”

Density

Cityhood proponents said incorporating would allow residents to have more direct say in their government on issues like zoning.

Cobb, once a Republican stronghold, has been at the forefront of Georgia’s shift to a purple state as younger, more diverse residents have been moving in.

Some long-time residents say they worry those new neighbors will bring big city problems like crime and traffic to their suburban haven, and proponents warned of looming threats like subsidized housing, laundromats and car washes being built adjacent to their bucolic back yards.

The no vote should not be interpreted to mean west Cobbers want that density, said state Rep. Ed Setzler, an Acworth Republican and sponsor of the bill to create Lost Mountain.

“One thing I know for sure is that, overwhelmingly, the citizens of west Cobb want to preserve the low-density rural, residential nature of west Cobb,” he said. “Overwhelmingly, 85 plus percent do. And the question was, is this objective better accomplished through a municipality, or is it better accomplished through maintaining our current government structures?”

Setzler says the correct answer is the former, and he charges the anti-city contingent with using conservative residents’ mistrust of government to dissuade them from supporting a measure he says would bring the people closer to their representatives.

“What was leveraged by the anti crowd was people’s general distrust of government,” he said. “They see the failure of the Biden administration in Washington, the untrustworthiness of the Biden administration, on the take from Ukrainian oil companies, they see those kinds of shenanigans happening at the highest levels in Washington, and they distrust government in general. So any anything, even a high-minded representative government effort like Lost Mountain is impugned by this broad sort of existential distrust of government.”

Warnings of out-of-control density rang hollow to many of the voters Dora Locklear spoke with. She is chair of West Cobb Advocate, a group opposed to cityhood.

“When you show up and you talk to your commissioner, and you’re familiar with zoning, and you know how those decisions are made, then there’s no room for misinformation and assumptions because a city government cannot come in and just arbitrarily rewrite zoning laws. That’s why we have a future land use map,” she said.

Locklear said proponents exaggerated the threat of high density developments being built near their homes. Residents’ current elected official, District 1 Commissioner Keli Gambrill, has been a stickler about zoning, she said.

“There were forty-something cases that took place that involved District 1, in not one of those was she outvoted, and there was only one that was not a 5-0 vote,” she said. “And in fact, in 22 of the cases, applications were withdrawn after she told the developer or the applicant that their request did not meet the future land use map or zoning and therefore she would not be recommending for approval.”

Gambrill said Cobb Commissioners defer to colleagues who represent districts where projects are proposed.

She, like the other commissioners, was publicly neutral on the cityhood measures, and said she was happy to have seen the community spirit on both sides of the issue. She also suggested there could be other ways to bring residents of unincorporated Cobb closer to their government.

“If we want to look at giving more representation, meaning fewer constituents to a commissioner, we can always look at expanding the board to seven or nine members, and then essentially having more districts throughout the county, that would again, give government closer to the people.”

That won’t solve the fundamental problem of non-local representation, Setzler said.

“If you go to seven commissioners, you’re still not going to be representing west Cobb,” he said. “It’s not going to be the majority in control of their backyard. That does absolutely nothing. It might take the representation of one elected official per 150,000 people down to one elected official per 120,000 people, but it’s nothing for the people of west Cobb who are being ruled by representatives they can’t vote for.”

Voters were also skeptical of claims their taxes would not increase, Locklear said.

“What made the biggest difference was when the voters and the people that we were connecting with connected the dots that the franchise fees that the feasibility study was claiming would make a $3 million surplus, once people understood who pays those franchise fees initially and they realized that they had been misled and they realized that it was coming out of their pocket, they were like, ‘No, this is not okay,’ she said.

Transparency

Cityhood opponents also claimed the process for the three cities was rushed when compared with other cityhood measures including Milton in north Fulton County, which incorporated in 2006.

“This happened very, very quickly,” said Bob Lax, a board member of the East Cobb Alliance, which opposed cityhood. “The substitute bill was introduced in January, it was voted on in February, it passed the governor’s desk by the end of February. That process in Milton was 14 months. So it was just run through super fast. There were a lot of unanswered questions. The financials of public safety were very concerning for most people, and they were concerned about losing those public safety services, which was my biggest concern as well.”

Smyrna Democratic state Rep. Teri Anulewicz compared east Cobb to its neighbor, Sandy Springs, which incorporated in 2005.

“With Sandy Springs, that process took decades,” she said. “And during that time, there were many, many, many open discussions of what exactly cityhood was going to mean to people who lived within the city limits, and that really didn’t happen with these cities,” she said.

“Because the legislative process was rushed, the bills that would have created these cities had the referendums passed were very sloppy,” she said. “And I remember reading these bills, the sponsors would say the city was set up in X way, and you’d read the bill, and the bill would say the city is set up in Y way. They didn’t match.”

A major bone of contention was the decision to place the measure on Tuesday’s ballot instead of November’s general election as originally planned. Opponents suggested the authors did so under the belief the primary would see higher turnout among Republicans, but the decision may have backfired, Anulewicz said.

“I think they were banking on lower turnout helping them,” she said. “What I think they vastly underestimated was the reality. I mean, everyone knows primary voters tend to be very educated, well-informed and motivated voters. And the cityhood movements clearly did not do an adequate job of making the case. The onus was on them. You’ve got to explain why people should make this choice to add a layer of government, and a lot of these are people who specifically live in those communities because they don’t want that additional layer of government.”

Setzler pushed back against that suggestion. The Lost Mountain vote was held in May so that, if the bill passed, residents could elect their first mayor and council in the November general election, which is likely to have higher turnout, he said.

What’s next

Lax said he’s planning to petition legislators to take another look at how cities are created. He’d like to create rules specifying that a city’s feasibility study match what’s in the cityhood bill lawmakers vote on, that the studies must be peer reviewed and require a certain amount of time between the release of a study and when a bill can be voted on.

Locklear also wants state action, including expanding feasibility studies to a five-year window and requiring them to consider the fiscal impact on the county new cities exit from.

“We cannot continue to be creating or approving these little piecemeal governments all over the state,” she said. “That’s not what the Georgia constitution is set up for. If we could address it at a state level, it doesn’t mean that no cities would ever form again, what it means is that the cities would be constitutional, and the voters will be informed on what they’re voting for.”

For now, pro-cityhood residents have no recourse but to hope the Board of Commissioners stick with their agreement to honor residents’ desire for a green, uncrowded community, Setzler said.

“The leaders in Cobb County who insisted that if Lost Mountain were voted down in the ballot, from Chairman (Lisa) Cupid to other commissioners and certainly Commissioner Gambrill, (they) would maintain the rural residential specialness, the rural residential nature of west Cobb, we’ll hold them to their word,” he said.

Other Cobb voters have one last chance at establishing a new city this year, in south Cobb’s Mableton, where voters will be asked to consider incorporating in November.

Mableton briefly became a city in the early 1900s, but disbanded a few years later after a major flood necessitated more money than city coffers could provide.

The fate of Cobb’s other three proposed cities should be a wake-up call to Mableton proponents, Anulewicz said, but efforts there are not doomed.

The added time for discussion helps, she said, and so does the fact that, unlike the three failed cities, Mableton’s proposed city government would operate in a similar way as Cobb’s existing six cities.

“I would recommend that they do a pretty detailed inquiry and post mortem and talk to people to see what happened, because they have six months to make their case to the voters, and I think that the voters didn’t appreciate being rushed for these votes,” she said. “But I think that if the Mableton supporters are transparent, if they supply answers to the questions, I think that they will have a much greater chance of success.”

Republican state Reps. Ginny Ehrhart and Sharon Cooper did not respond to requests for comment, nor did Preserve West Cobb, a pro-cityhood group. East Cobb Cityhood, a pro-cityhood group for East Cobb, set its Facebook page to private and scrubbed its website.

Georgia Recorder is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Georgia Recorder maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor John McCosh for questions: info@georgiarecorder.com. Follow Georgia Recorder on Facebook and Twitter.