By Gareth Dorrian, University of Birmingham [This article first appeared in The Conversation, republished with permission]

A launch window – the period during which a rocket must be launched to reach its destination – opens on August 29 for the first flight to the Moon since 1972 by a spacecraft designed to carry humans there. If all goes well, the Artemis project will be on track to meet its goal of putting humans back on the Moon in 2025.

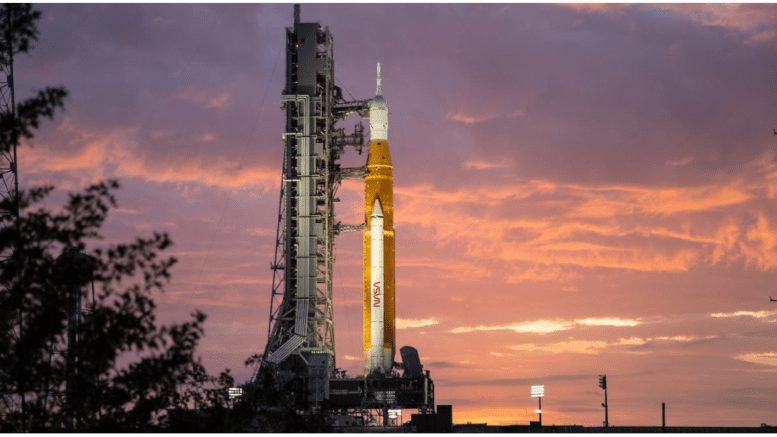

Project Artemis, the namesake of the sister of Apollo and daughter of Zeus in ancient Greek mythology, is designed to establish a long-term human presence on our nearest celestial neighbour, and to ultimately explore even further afield. Artemis 1 is the first of several missions. It consists of Nasa’s new super-heavy rocket, the Space Launch System (SLS), which has never been launched before, and the Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle (or Orion MPCV), which has only flown in space once.

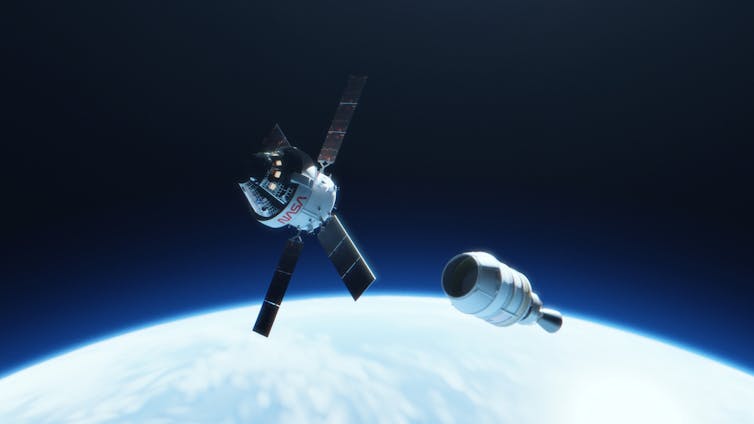

Unlike the Command Service Modules of the Apollo missions, which were powered by hydrogen fuel cells, the Orion MPCV is a solar-powered craft. Its distinctive X-wing style solar arrays can be swept forward or backward to reduce stress on the probe during high-thrust manoeuvres. It is capable of carrying six astronauts for up to 21 days in space. The imminent, uncrewed Artemis 1 mission, however, may last as long as 42 days.

Also unlike Apollo, Artemis is an international project. The Orion MPCV consists of a US-built capsule for the astronauts and a European-built service module containing supplies of fuel, water, air, solar-arrays and rocket thrusters.

The reliance on the Sun for power places some restrictions on when Artemis-1 can launch as the geometry of the Earth and Moon have to be such that the Orion spacecraft is not in shadow from the Sun for over 90 minutes at any point during the flight. The earliest launch window opens at 08.33 EST on August 29, with further windows on September 2 and 5.

Pioneering flight

The SLS will put Orion into Earth orbit, where its core stage will be discarded – dropped into the ocean. Most of the energy required to fly a spacecraft to the Moon is used in this first phase of the flight, just to reach low-Earth orbit. Orion will then be pushed out of Earth orbit and onto a lunar-bound trajectory by the second stage of the SLS, called the interim cryogenic propulsion stage (ICPS).

Orion will then separate from the ICPS and spend the next several days coasting to the Moon. The launch is typically one of the riskiest parts of any spaceflight, especially for a new rocket. If Artemis-1 successfully reaches Earth orbit it will be a significant milestone for the project.

During the mission, Orion will also deploy ten mini satellites known as CubeSats. One of these, BioSentinel, will contain yeast to observe how the microgravity and radiation environment on the Moon affect the growth of microorganisms. Another, NEA Scout, will deploy a solar sail and then fly to a nearby asteroid for a close-up examination. Meanwhile, IceCube will orbit the Moon and search for ice deposits on or near the surface, which may be used by future astronauts.

Entry into lunar orbit will occur just 60 miles above the lunar surface. Orion will fire its onboard thrusters to slow the spacecraft and allow the Moon’s gravity to capture it into orbit. It will orbit the Moon in an unusual, distant retrograde orbit – in the opposite direction to the Moon’s spin. This particular orbit was originally chosen to flight test Orion as part of a now-cancelled mission to learn to redirect asteroids.

During this phase, Orion will travel up to 70,000 km from the Moon and reach the furthest distance from Earth ever for a human-capable spacecraft. If astronauts were onboard, they would have a grand view of the distant Earth and the Moon.

Orion will spend between six and 23 days in lunar orbit, after which it will fire its onboard thrusters once again to accelerate out of lunar orbit and place itself on a return to Earth trajectory.

The surface of the Moon can reach 120°C during the day and drop to -170°C at night. Such large temperature changes can cause significant thermal expansion and contraction of materials, so the Orion spacecraft had to be built with materials able to withstand significant thermal stress without failing. One goal of the mission is to check this, and crucially, ensure that the breathable atmosphere inside the capsule is maintained throughout.

At the distances of the Moon, astronauts would also be outside of the Earth’s magnetic field, which normally protects us from cosmic radiation. Deep space radiation is a serious concern for any future human missions to the Moon. The longest Apollo mission (Apollo 17) lasted 12 and a half days – Orion will be in deep space for three to four times as long. Engineers will, therefore, also keep a close eye on the radiation environment inside the capsule.

On returning to Earth, the Orion crew capsule will separate from the service module, which will be discarded, and then enter the atmosphere protected by its heat shield. It will descend and deploy parachutes to land at sea. In fact, this is the most crucial part of the mission: to ensure that the capsule can survive the high re-entry speeds of a spacecraft returning from the Moon and then make a safe landing. To do so, the heat shield must endure temperatures of 2,750°C while Orion decelerates from 24,500 miles per hour – that’s significantly hotter than the temperatures encountered when spacecraft return from low-Earth orbit.

Assuming a successful launch on August 29, the splashdown would be on October 10.

Artemis-2, currently slated for launch in 2024, will carry four astronauts on a lunar flyby some 9,000km above the Moon’s surface. The astronauts on Artemis-2 will become the record holders for the greatest distance from Earth ever reached by humans.

Nasa has also just announced a short list of landing sites near the Moon’s South Pole for the first lunar landing mission, Artemis-3, aiming to land humans there in 2025. Whether they reach that goal will ultimately depend on how things go for Artemis-1.

Gareth Dorrian, Post Doctoral Research Fellow in Space Science, University of Birmingham

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.