by Lynn Greenky, Syracuse University, [This article first appeared in The Conversation, republished with permission]

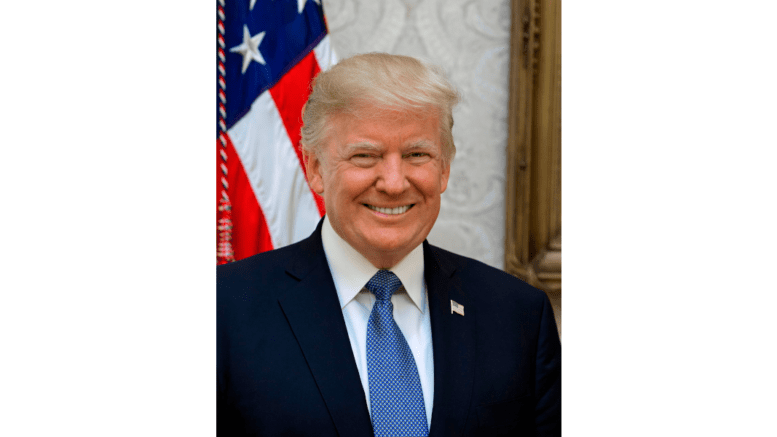

In each of former President Donald Trump’s four indictments, he has been allowed to stay out of jail before his trial so long as he abides by certain conditions commonly applied to most people accused of crimes in the U.S.

In the federal case in Washington, D.C., that concerns Trump’s alleged efforts to overturn the 2020 election, Trump is under a protective order barring him from speaking to people involved in the case except through or with his lawyers. In a document unsealed on Sept. 15, 2023, special counsel Jack Smith has also asked the judge in that case to issue a “narrow, well-defined” gag order against Trump to protect witnesses and the jury pool. In the New York state case regarding alleged falsification of business records, Trump has been ordered “not [to] communicate about facts of the case with any individual known to be a witness, except with counsel or the presence of counsel.” In the federal case in Florida, about his handling of classified documents, he is under a similar order.

In the Georgia racketeering case about the alleged attempt to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election, Trump’s bond agreement imposes limits like those imposed by the other judges and also says he may not intimidate or threaten anyone involved in the case, including by posting on social media.

Trump has objected to all of these restraints, saying they limit his First Amendment rights to free speech – and in particular his right to discuss the cases while campaigning for the presidency.

As an attorney, professor and author of a book about the boundaries of the First Amendment, I see all of those orders as efforts to, in fact, protect both Trump’s First Amendment speech rights and his rights under another part of the Constitution – the Sixth Amendment, which guarantees the right to a fair trial.

Protecting Trump’s rights

Key to a fair trial is the idea that the defendant is innocent until proven guilty. That means the jury must be free of bias against either the defendant or the prosecution and open-minded to assessing guilt or innocence based on the evidence presented in court without regard to any outside influences.

All the orders Trump is subject to are designed to protect that presumption. To do so, they limit his ability to speak publicly about the cases against him, but they do so within the limits of the Constitution.

The federal protective order imposed by D.C. District Court Judge Tanya Chutkan ostensibly limits Trump’s ability to share evidence collected by the Department of Justice in its investigation of the conspiracy and obstruction crimes with which he is charged. However, in an Aug. 11, 2023, hearing, the judge made clear that she intends to safeguard the integrity of the proceedings both inside her courtroom and in the court of public opinion. To that end, she warned that all parties take “special care to avoid prejudicing the jury pool or intimidating witnesses.”

The Georgia bond order adds specificity to that warning and bars Trump from making any direct or indirect threats by any manner, including posts and reposts to social media, against his co-defendants, unindicted co-conspirators, witnesses or victims of his alleged crimes.

These limits without doubt restrict Trump’s ability to speak freely – but they’ve been imposed because his own actions led to criminal charges. And the courts are bound to protect his constitutional right to defend himself before an unbiased jury, even if he prefers to speak more freely.

In any event, First Amendment rights have often been subject to restrictions based on when, where and how a person speaks, for the purpose of balancing free speech with other competing social purposes. For instance, the reason someone may not yell “fire” in a crowded theater if there is not an actual fire is the resulting threat to everyone else’s safety.

Both the First Amendment right to freedom of speech and the Sixth Amendment right to a fair trial serve individual interests, but also the interests of society at large.

In Trump’s cases, the restrictions on his speech are to protect his right to a fair and impartial jury pool, as well as society’s right to hear testimony from witnesses who are not afraid to tell the truth.

The courts of law and public opinion

Trump has a right to speak – and the public has a right to be allowed to listen if they wish. In fact, the audience’s rights are often one key protection against censorship of a speaker. A criminal defendant’s First Amendment right to publicize his theory of the case protects not only his interests, but also the interests of the public, by serving as a check on overreaching by the prosecution or the judge.

However, the court of public opinion – in legal terms, the public forum – remains a relatively ungoverned space. A speaker can generally make all manner of statements, whether true or false, as long the statements do not incite lawless action or terror in the audience.

But the same is not true of the courtroom. Speech there is constrained by rules of evidence, which are designed to protect the principles and standards of the criminal justice system; “[l]egal trials are not like elections, to be won through the use of the meeting-hall, the radio, and the newspaper,” as Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black put it in a 1941 ruling. In other words, a defendant’s Sixth Amendment right to be judged by an unbiased jury of their peers combines with the right of the public to justice and fairness in court proceedings.

Threats and intimidation targeted at participants in a criminal trial jeopardize the judicial system. Unfiltered evidence published outside of the courtroom can hamper the abilities of all parties to move the case forward quickly, affect testimony of witnesses at trial and infect the jury pool – making it difficult to find a group that will judge the case only upon evidence introduced at trial.

Trump has not been silenced. Even in the face of all four orders in place, and any gag order that might be issued, he still retains his First Amendment right to assert that the federal and state charges against him represent a miscarriage of justice. He can demand scrutiny of the motivations behind his prosecutions. However, he may not use that right to subvert society’s constitutionally protected right to the integrity of the criminal justice system. First Amendment protections are not absolute; simply because someone seeks to communicate does not guarantee its full protection. It is not his thoughts and opinions that are being restricted by the protective order or the bond order – it is the manner in which he expresses them.

At the conclusion of the proceedings, of course, many of the speech restrictions will be lifted, and Trump can speak his piece with the megaphone that the press is sure to provide.

This is an updated version of an article originally published Aug. 28, 2023.

Lynn Greenky, Professor Emeritus of Communication and Rhetorical Studies, Syracuse University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.