By Clark D. Cunningham, Georgia State University [This article first appeared in The Conversation, republished with permission]

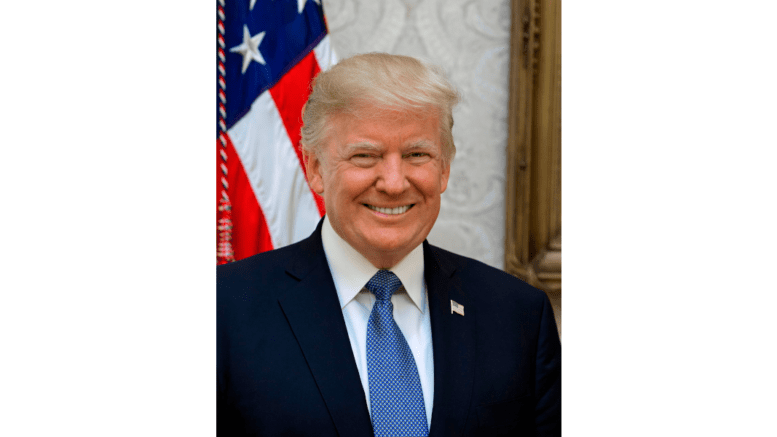

A court filing by the Justice Department just minutes before midnight on Aug. 30, 2022, was a sharply worded attack on former President Donald Trump’s request for a so-called “special master” – a neutral arbiter – to review the documents the FBI seized at his estate, Mar-a-Lago, earlier in the month.

Bottom line: The Justice Department says the documents don’t belong to Trump and says someone has deliberately concealed documents marked classified from a federal grand jury investigation. The department has not yet publicly stated who they believe is guilty of this crime – whether Trump himself, members of his team, or both.

In the filing, the Justice Department wrote, “The government also developed evidence that government records were likely concealed and removed from the Storage Room and that efforts were likely taken to obstruct the government’s investigation.”

This latest revelation has prompted observers to say that obstruction of justice charges are at stake. But that’s a broad term that covers many wrongful acts. The specific crime at issue here is obstructing a federal investigation.

The Conversation asked Georgia State University legal expert Clark Cunningham, an authority on search warrants, to describe the meaning of obstruction, and why Trump may be charged with this crime.

The crime of obstruction, and a particular version of it

There are 21 different federal crimes that involve obstruction of justice. One of the obstruction laws, called Section 1519, is violated if someone “knowingly conceals any document with the intent to obstruct” – or block – a federal investigation. That’s obstruction of a federal investigation, and conviction for this crime can result in up to 20 years of prison.

For example, Jesse Benton, who managed Ron Paul’s 2012 presidential campaign, was convicted of violating Section 1519 when he concealed improper campaign payments from the Federal Election Commission. Trump later pardoned Benton in December 2020.

The FBI cites Section 1519 in its Mar-a-Lago search warrant and in the recently unsealed affidavit submitted to a Florida court to obtain the warrant. But until the Department of Justice’s Aug. 30, 2022, midnight court filing, the public did not know what kind of concealment and what kind of obstruction the department was alleging Trump committed.

Why the government alleges this crime was committed at Mar-a-Lago

A federal grand jury subpoena demanded on May 11, 2022, that Trump turn over all documents with classified markings to the government.

The FBI was informed by Trump representatives in a sworn statement at Mar-a-Lago on June 3 that all documents marked classified were being turned over that day. This statement has now been proved to be false.

Trump was aware of the FBI’s June 3 visit to Mar-a-Lago. In his own court filings he has said that he personally met the FBI agents when they arrived.

Despite the sworn statement that no more documents marked as classified remained at Mar-a-Lago, the FBI found 76 documents marked classified in a storage room during its subsequent Aug. 8, 2022 search of Mar-a-Lago. They also found documents marked “Top Secret” in a container in Trump’s private office. The agents also seized a desk drawer in that office containing documents marked classified that were mixed in with other items, including Trump’s passports.

The government believes that the false statement made to the agents on June 3, as well as other evidence they have not yet disclosed, shows there was a deliberate plan to conceal documents that should have been given to the grand jury.

Before the Aug. 30 filing, it appeared that Trump’s most serious risk of criminal liability involved violating the Espionage Act by willfully retaining documents relating to national security after he left office. Revelation of these new details emphasize another offense to be added to the list of his possible crimes: obstruction of a federal investigation.

Clark D. Cunningham, W. Lee Burge Chair in Law & Ethics; Director, National Institute for Teaching Ethics & Professionalism, Georgia State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.