by Arielle Robinson

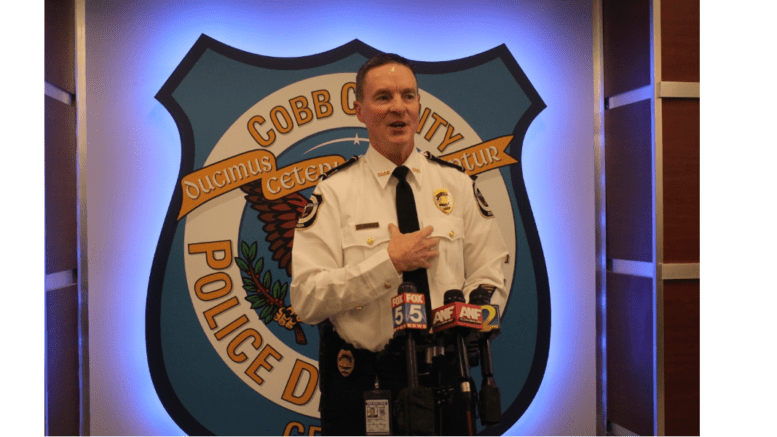

“We do not surveil our citizens. That is not what facial recognition does in this realm at all. I won’t say that other governments don’t do that, I won’t say that other countries don’t do that. We are not setting up cameras at sporting venues to watch the audience come in to see if we can find wanted people—that is not what we’re doing with this product,” Cobb County Police Chief Stuart VanHoozer said during a press conference at police headquarters in Marietta Friday morning.

The press conference followed a unanimous vote Tuesday by the Cobb Board of Commissioners allowing the police department to use facial recognition technology to identify suspected criminals and unidentified victims.

The BOC approved the CCPD entering a three-year contract with Clearview AI, a facial recognition company.

An article by the AJC reported that Clearview AI has faced controversy for some of its data collection practices, including collecting biometric data without consent and gathering images of social media.

VanHoozer and the CCPD held Friday’s press conference to clear up concerns about how the police plan to use the technology.

“We cannot get your doorbell images from your house, that’s not what this product does. This product does not see you when you leave your house and take your kid somewhere, as has been alleged. It’s not what we do,” VanHoozer said.

“There are no street cameras taking pictures of you and putting it into our database,” he said. “Streetlights are not gathering your information. We don’t own your face, there is none of that going on. We would not participate in that and the people below me would never bring me a product that surveils its citizens—because we are citizens. The police are the community and the community are the police. That’s just not true, it’s not accurate, and if it was true, we couldn’t hide from it, but we would never do it. And the Board of Commissioners would never let us do it even if we wanted to.”

VanHoozer said that while some concerns at Tuesday’s BOC meeting were legitimate, and many were well-intentioned, some were not legitimate.

Here are several highlights from Friday’s press conference.

What the police say they are using the technology for

“The vast majority of what we’re going to use this for is when we have a still photograph of the suspect of a crime and we want to identify that individual, we will put that picture into the system, the system will give us results, and then we will start our investigation,” VanHoozer said.

Once the police put the still photograph into the Clearview AI system, the system begins scanning the over 10 billion publicly available images the system has collected from the internet to make a match. Images collected and searched can include social media pictures and profiles made public, such as on Instagram, Facebook, and TikTok.

VanHoozer called the number of photographs they have that can be compared to others in the database “the gallery.”

“Any publicly available image and legally obtained image is what this database gives us that the other one did not,” VanHoozer said.

The police chief said the acquiring of public images across the internet is what makes Clearview AI different from facial recognition technology the police have used in the past.

“The product that we had before was just booking photos,” VanHoozer said. “That was very problematic because those booking photos were not updated. We have old booking photos there, it’s almost impossible to get updated booking photos from the sheriff’s offices around metro Atlanta into our database. This one [Clearview AI] is not booking photos only. Anything that can be seen legally that’s available to the public on the internet is available to us.”

VanHoozer said there are some outliers the police may use from time to time in identifying people.

“Like somebody with dementia who cannot identify themselves in the field,” he said. “If we have that, yes, we feel like it’s legitimate for us to be able to take that individual’s picture and put it into our system.

“If we have a deceased individual, a homicide victim as we’ve seen this year quite often, we can put that in. So there are some other legitimate reasons that we could use it for outside of a suspect, but for the most part, most of what we’re going to be doing is trying to identify a suspect who we’ve captured a picture of during the crime. That’s pretty much the main thing we’re going to use this for.”

VanHoozer said the system has been well-vetted through the court systems, and that there is no reasonable expectation of privacy for things that people put online.

The police’s crime analysts already manually search online and through social media to try to solve crimes, he said.

The use of facial recognition by police is not entirely new

As mentioned already, VanHoozer said Cobb County has used facial recognition technology for several years now.

“We have been using this for a while and it’s not a technology that is foreign to police agencies,” VanHoozer said. “We’ve been watching this mature for a number of years, we’ve been making sure that there are no constitutional violations—not just in my opinion, but in the court of law.”

VanHoozer says the police have been studying Clearview AI for at least two years.

CCPD began a seven-month trial with Clearview AI in January.

VanHoozer sought out a longer contract in June but BOC Chairwoman Lisa Cupid and members of the community, including the Cobb Coalition for Public Safety, delayed the vote until further details on the technology were provided.

“We have now found a vendor who is just a better vendor. It’s more returns, more accuracy, much-improved safety for our community, which is really the bottom line,” VanHoozer said Friday.

How effective is Clearview AI technology?

VanHoozer said the technology has been very effective since the police started using it and is just effective overall.

“We have seen multiple cases that we have been working on for a long period of time that were solved with facial recognition in a matter of seconds,” he said. “When we get a match or what we believe to be a match in a facial recognition program, we then do an investigation.

“A facial recognition match is nothing really more for us than a tip. It could be a tip from a citizen on a phone who calls in and says ‘hey, I think I know who did this crime…’

“If we get something like that from our community, we don’t immediately go get a warrant. We actually do an investigation to see if that person—if there’s evidence either exculpatory or damaging for him that he actually committed a crime.

“That’s how we use facial recognition. If we get a match, we then start an investigation to see if that person did or did not commit the crime. And if we get evidence that the person did that crime, then we continually refine that information, go to a supervisor, and then seek a warrant if the evidence suggests that he did in fact do that,” VanHoozer said.

The police chief then pointed to the success of the former vendor’s facial recognition technology.

“The very first [crime] we tried—and this was not with Clearview—was a commercial burglar who had hit all over metro Atlanta that everybody in metro Atlanta was looking for,” he said. “We were wasting a lot of time doing manual labor to try to identify this individual, doing what we call BOLOs—lookouts, sending them to all the agencies around here asking our officers to go out in patrol cars and see if you can locate this individual. We didn’t have a tag number, all we had was surveillance video.

“Literally, in a matter of seconds, we got a match within our facial recognition system. We were able to do an investigation on that subject and find out that he was responsible for multiple burglaries all over Atlanta. That was our very first one. We used that facial recognition company for a while.”

VanHoozer said several suspects and victims have been quickly identified with the use of Clearview AI.

“We had an agency that was testing Clearview several years ago,” he said. “They called and said ‘do you have any faces?’ We had a face, we had a picture of an individual that we suspected had killed a young man who was just dumped out on the side of the road. We didn’t find him for a few days. It was unsolved, we just kept trying to solve it over and over and over by putting it out in the media, putting it out in south Georgia where we thought the suspect might be.

“Seven seconds it took us to solve that crime with Clearview AI. Clearview was a bad word at that time in the media. We elected to study it, to watch it, to see ‘hey, is it legitimate?’ Are they doing things that are legitimately concerning to us? Are agencies doing things with it that are legitimate concerns to us, and what we found out was yes, there were some things we were concerned about.

“So we watched it mature and started to determine whether or not we could mitigate some of those things with policy. Over the years, that technology has gotten better. The company has worked out many of the issues that it had with various agencies and rules and regulations in various locations, and so we elected to go forward with a test this year.

“So we did that. The effect again was incredible. We found homicide suspects, homicide victims, it’s very important that we identify a victim very quickly because whoever killed that individual is going to be getting rid of blood, weapons, and other physical elements. We have to figure out who that victim is very quickly in order to get to that short-lived evidence.

“I believe we have identified three or possibly four victims of homicide, we’ve identified homicide perpetrators, and countless other perpetrators. We’ve gone into the child trafficking arena and we were able to identify young people involved in that trade. So it is effective.”

What about potential biases in the system?

Among the concerns brought up at Tuesday’s BOC meeting was the potential for bias, especially against people of color.

VanHoozer said Tuesday and Friday that Clearview AI is extremely accurate.

“The NIST…the National Institute of Standards and Technology—it’s a government body that tests various things, but one of the things that it tests is facial recognition. So you can submit your algorithm to the NIST and they will actually test it across various demographics, genders, to see the general accuracy of it but also the accuracy between races.

“It’s no longer what it was 15 years ago—this has been refined to the point where this is actually very accurate technology. But when they [NIST] studied the differences between the races, they found that there was virtually no difference. For Clearview AI, the lowest performing race was Caucasian and that was 99.7 percent accurate. That was the lowest there. Across all races, they were over 99 percent accurate, so it’s almost 100 percent accuracy,” he said.

Chief explains the department’s facial recognition process

VanHoozer explained not all of Cobb’s police officers have access to the Clearview AI technology.

When an officer has a still photograph they are required to go to a special unit that has been trained on how to handle the facial recognition technology.

“We have it confined to a small group of people who specialize in this,” VanHoozer said. “We do that for a reason. Number one, if the detective wants to run somebody in the system, that gives us a chance to make sure it’s legitimate.

“They have to give us a couple of things. They have to give us a legitimate law enforcement reason so they can say ‘hey, this is a commercial burglar we’ve been looking for for a while, they’re wanted in other areas of the county or the metro Atlanta area’…it could be whatever the crime is.

“They have to give us a case number, because then we can verify that that is actually a case that is involving a crime like this and we do have video surveillance from that case where they got the picture. The facial recognition unit will actually run that information and when they get it back, they’ll send leads back to the detective.”

VanHoozer again emphasized the point that an officer must complete an investigation once a match is found.

“He cannot just go get a warrant no matter how similar those faces look,” VanHoozer said. “He has to do an independent investigation and make sure that he has evidence that the individual committed a crime.

“Before that, actually, we also have a peer review. So the facial recognition operator has to actually have an independent, secondary facial recognition operator to do a more or less blind review so that we make sure that there is going to be at least a good viable lead.

“So the detective does his investigation, he gets either exculpatory evidence that says, ‘hey, this is not the right person,’ or he gets evidence that the person did commit a crime. He is bound by policy, you cannot get a warrant at that point.

“Under normal circumstances without facial recognition, you could get a warrant all day long. But we require that he go to his supervisor to get an actual warrant. Once the supervisor weighs in on that—the only reason he has to do that is because we’re using facial recognition and we want our community to know ‘hey we’re going to be careful with this’—once the supervisor says yes, you got your compliance with policy, you’ve got enough independent evidence to take a warrant, then they go to a judge.

“You got to prove the whole thing to a judge. So, we feel like we have safeguards in place that mitigate a lot of the concerns of our community. Some of the allegations of what this product does is not at all what it does, and it’s very, very effective and efficient for our community.”

VanHoozer says community members are coming around to the technology

“We met with the ACLU and what a great meeting…what they helped us see is what we missed,” the police chief said. “And I consider them a community partner. Even though we didn’t discard the program as they wanted us to, they did help us strengthen our policy. And they did help us to review a couple of questions we didn’t think of.

“And that’s why we’re pretty slow with our policy. We wanted to go to the BOC meeting before we put the policy out so we can hear what people say, we wanted to talk to the media, and we wanted to talk to the people that were trained inside the department. We did that yesterday. So we’ll be wrapping that up.”

VanHoozer said he had spoken with some people who were iffy about the technology but then came around once they saw how it would be used.

“We have never hidden from facial recognition or license plate recognition,” he said. “…We hope in the long run that we can look backward on this and our community is so supportive of facial recognition. I believe they will be. We already see it—when we actually survey and we actually tell our story, it’s very strong, very strong.”

Arielle Robinson is a student at Kennesaw State University. She also freelances for the Atlanta-Journal Constitution and is the former president of KSU’s chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists as well as a former CNN intern. She enjoys music, reading, and live shows.