by Darryl K. Brown, University of Virginia, [This article first appeared in The Conversation, republished with permission]

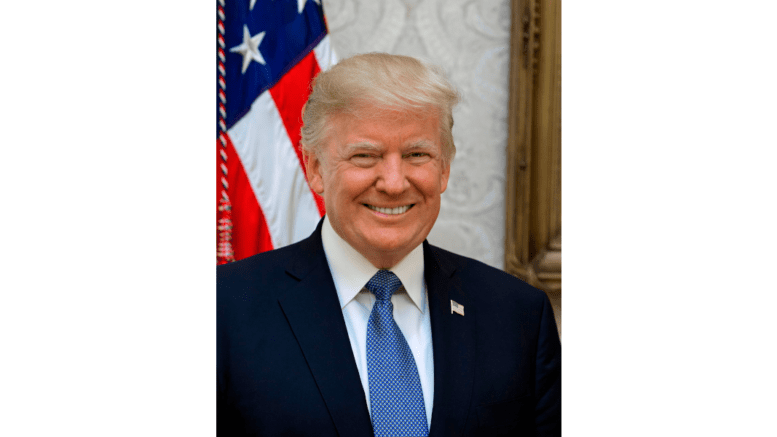

A federal grand jury in Florida indicted former President Donald Trump on June 8, 2023, on multiple criminal charges related to classified documents he took from the White House to his home in Mar-a-Lago, Florida, according to multiple sources cited in The New York Times and The Associated Press.

Trump himself said on his social media outlet, Truth Social, that he had been indicted.

The seven counts against Trump – the first president to face federal charges in U.S. history – include obstruction of justice, false statements and willful retention of documents, The New York Times reported.

Trump said he was set to appear in a Miami federal courthouse on June 9 at 3 p.m.

The Justice Department did not immediately comment on the reported charges.

But the federal charges come on top of other legal trouble Trump is facing at the state level.

Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg charged Trump in April 2023 with 34 felony counts of falsifying business records.

And in Georgia, the Fulton County district attorney is investigating Trump’s alleged attempts to overturn the results of the 2020 election. This, too, could result in criminal charges under Georgia law.

If a person is charged by federal and state prosecutors – or prosecutors in different states – at the same time, which case goes first?

Who gets priority?

I am a scholar of criminal law. It’s important to recognize that criminal law provides no clear answer how to settle that question.

No law dictating a path ahead

Nothing in the U.S. Constitution or federal law dictates that, say, federal criminal cases get priority over state cases, or that prosecutions proceed in the order in which indictments are issued.

The solution ordinarily is that the various prosecutors will negotiate and decide among themselves which case should proceed first. Often, the one that involves the most serious charges gets priority, although the availability of key witnesses or evidence could play a role.

There are a few cases to look to as reference for state charges competing with federal ones.

After neo-Nazi James Fields drove his car into a group of protesters at the Unite the Right Rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017, killing one person and injuring others, he was charged with crimes in both federal and state courts.

The state homicide trial went first. Then, Fields pleaded guilty to federal hate crime charges after the state conviction and received two life sentences for his crime from both the state and federal charges.

By contrast, “D.C. Sniper” John Allen Muhammad was finally apprehended at a highway rest stop in Maryland in 2002, after a deadly series of sniper shootings in Maryland, Virginia and the District of Columbia, which killed 10 people and injured three.

Maryland police arrested Muhammad. Then, federal officials were the first to file charges. But Muhammad was first put on trial and convicted of murder in Virginia.

Trump’s circumstances

In Trump’s case, his federal charges – which were not unsealed as of June 8 – are likely to carry longer potential sentences than the state offenses.

The felonies he is facing in New York are white-collar crimes and may not result in any prison time, legal experts have said.

Of course, much about Trump’s case is unique. Never has a former president faced federal or state prosecution. That fact alone probably makes priority for the federal prosecution more likely.

An active presidential candidate has faced criminal charges in the past, though.

Socialist Party nominee Eugene Debs was prosecuted and convicted under the Espionage Act for his opposition to World War I in 1918. He campaigned from prison for the 1920 election, before losing to Republican Warren G. Harding.

Federal authorities could assert priority over state officials by taking custody of the defendant. States cannot arrest suspects who are outside the state’s borders, but federal law enforcement officers can arrest suspects anywhere in the country.

It is exceedingly unlikely that federal prosecutors would ask a court to detain Trump in jail before trial. Rather, they are likely to allow him to be released on bail as the New York court did in April. But their nationwide jurisdiction gives federal authorities an advantage over states in controlling the defendant, in terms of placing and enforcing bail conditions, for example, regardless of where he resides at the moment.

Darryl K. Brown, Professor of Law, University of Virginia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.