by Stefanie Lindquist, Arizona State University, [This article first appeared in The Conversation, republished with permission]

For the past 50 years, Republican policymakers and judges have sought to bolster federalism in the United States. Since Ronald Reagan’s first inaugural address in 1981, Republicans have been calling for policymakers to rein in the federal government in favor of devolving more power to the states.

Contrary to what it sounds like, “federalism” does not mean a strong central government. Instead, it refers to a system of government in which the people may be regulated by both the federal and state governments.

Reagan succinctly expressed it in his 1981 inaugural speech: “It is my intention to curb the size and influence of the Federal establishment and to demand recognition of the distinction between the powers granted to the Federal Government and those reserved to the States or to the people.”

All U.S. citizens are actually citizens of two separate governments: They are citizens of the United States as well as citizens of the state in which they live. And they are subject to two systems of law as a result.

The Framers valued federalism – and the division of power between different levels of government – as a bulwark against tyranny and a protector of liberty.

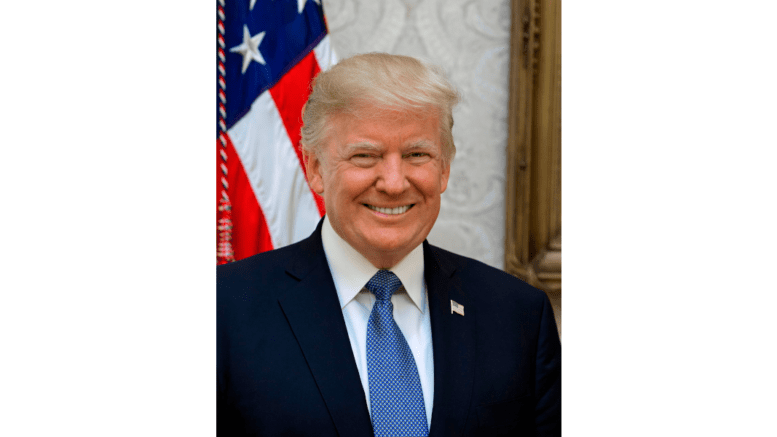

But this division of power has doubled the trouble for the leading Republican in the country: former president and likely GOP presidential nominee Donald Trump, who now stands indicted on 13 criminal counts by a Fulton County, Georgia, grand jury for “knowingly and willfully” joining “a conspiracy to unlawfully change the outcome of the election.” Eighteen others were also indicted on a variety of charges related to the attempt to overturn the election.

Prosecutions by ‘separate sovereign governments’

With federalism come two sources of law – state and federal – which creates a complex web of regulations that can lead to criminal charges at both the state and federal levels, even for the same behavior.

While this may sound like a violation of the constitutional ban on double jeopardy, that constitutional protection only applies to repeated prosecutions by the same sovereign government. The state and federal governments are separate sovereign governments.

The federal government may criminalize behavior within the constraints imposed by the U.S. Constitution that limit federal power. Most federal crimes involve some form of interstate travel or transactions, for example. But the states’ criminal codes may often regulate the same behavior or additional behaviors with different standards and different penalties.

For example, when Timothy McVeigh blew up the federal building in Oklahoma City in 1995, he was subject to prosecution by both state and federal officials for violations of the laws of both governments.

McVeigh committed federal crimes, such as use of a weapon of mass destruction on federal property and the murder of federal law enforcement officers. The state of Oklahoma [could also have prosecuted him] for violating Oklahoma murder statutes, among other state criminal violations, although once McVeigh was convicted and sentenced to death in a federal trial, Oklahoma prosecutors did not ultimately seek to bring a case against him.

Donald Trump is now experiencing the full weight of a system of government in which criminal law is produced and enforced by law enforcement agencies and prosecutors across 50 states and by one powerful central government.

The ‘very essence’ of federalism

Trump’s activities in Georgia and New York may be prosecuted independently by state prosecutors – district attorneys and state attorneys general – under those states’ criminal codes.

At the same time, many of the facts implicated in the Georgia and New York cases could contribute to, or be relevant to, federal criminal prosecutions as well.

Prosecutions at both levels represent the very essence of federalism in action.

Usually in such circumstances, state and federal prosecutors must negotiate with one another about who will bring their prosecutions first, and how the state and federal trials will be managed and accommodated by each government.

But no matter what, neither set of officials has the power to deny the other the chance to prosecute a defendant who has violated the laws of their respective jurisdictions.

There is abundant irony in the fact that federalism – championed by Republicans and conservative judges for decades – now has come to haunt the leading Republican for the U.S. presidency.

And even more ironic is that even if he becomes president again, Donald Trump will not have the authority to pardon himself – if that is even constitutional – or anyone else for the violation of state crimes.

Presidential pardon authority extends to federal crimes alone.

Stefanie Lindquist, Foundation Professor of Law and Political Science, Arizona State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.