By Melanie Dallas, LPC

[This guest article is by Melanie Dallas LPC, the CEO of Highland Rivers Behavioral Health]

It is perhaps an odd twist of history that fewer people know the name Lois Curtis than the name of the man she sued. Tommy Olmstead was commissioner of the Georgia Department of Human Resources – which in the 1990s oversaw the state’s mental health services – and it is his name by which one of America’s most important civil rights cases for people with disabilities continues to be known.

Olmstead v. LC, or “Olmstead” as it is usually called, was a 1999 decision by the U.S. Supreme Court. Based on principles of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), the Olmstead decision said that people with disabilities – whether mental illness, cognitive impairment or other conditions – could not be institutionalized simply because they have a disability. Further, people with disabilities have a right to receive state-funded services and supports necessary to live in their community.

Like so many Supreme Court decisions that become the law of the land, this ruling can be traced back to a single individual. In this case that individual is Lois Curtis, the “LC” in Olmstead v. LC, who deserves to be recognized during Black History Month alongside every other civil rights pioneer.

Lois Curtis was born in Atlanta in 1967 and lived with both a mental health condition and cognitive disability. Her family struggled to meet her needs. She was known to wander off and go missing; police would sometimes take her to jail and other times to a psychiatric hospital. Beginning at age 11, and for the next 20 years, Lois was in and out of Georgia Regional Hospital Atlanta many times. Her wish was to live in the community, but services to support her there simply didn’t exist – and when she would struggle, she would be returned to the hospital.

In May 1995, Susan Jamieson, an attorney with the Atlanta Legal Aid Society, filed a lawsuit in federal court on behalf of Lois Curtis, challenging her confinement at Georgia Regional Hospital. A second plaintiff, Elaine Wilson, also from Georgia, was allowed to join the case the next year.

In March 1997, the court ruled in the plaintiffs’ favor, noting that Georgia’s failure to provide appropriate community-based treatment for the women violated Title II of the ADA. The State of Georgia appealed to the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals, which again ruled in Lois and Elaine’s favor. The state then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court; oral arguments took place on April 21, 1999.

When the Supreme Court handed down its decision in June 1999, every state was suddenly faced with the prospect of building and ensuring community-based services and supports for individuals with mental illness and disabilities.

In Georgia, much of that work has fallen to Community Service Boards like Highland Rivers Behavioral Health, which not only provide community-based primary behavioral healthcare, but also highly-intensive services for individuals with high-acuity needs. The Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) program was conceived as a “hospital without walls” specifically to support individuals living in the community who in the past may have been institutionalized.

Over the past 24 years, states have worked to move individuals out of hospitals and into their communities. A post-Olmstead lawsuit in Georgia arguing the state is not doing this fast enough resulted in ongoing oversight by the U.S. Department of Justice. Like many other states, progress has been made but much work remains to be done.

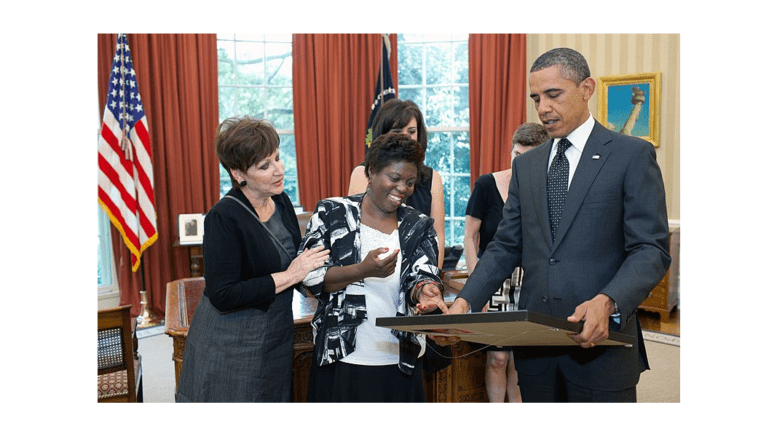

Lois Curtis was able to live out her days in her community of Clarkston, Georgia, receiving the support she needed and becoming a well-known artist. Unfortunately, she passed away last November at age 55. But because of her, hundreds of thousands of Americans with mental health conditions and disabilities are able to live their lives in their communities. It is a legacy that is not only meaningful during Black History Month, but every day of the year.

Melanie Dallas is a licensed professional counselor and CEO of Highland Rivers Behavioral Health, which provides treatment and recovery services for individuals with mental illness, substance use disorders, and intellectual and developmental disabilities in a 13-county region of northwest Georgia that includes Bartow, Cherokee, Cobb, Floyd, Fannin, Gilmer, Gordon, Haralson, Murray, Paulding, Pickens, Polk and Whitfield counties.