By Samuel Perry, Baylor University [This article first appeared in The Conversation, republished with permission]

In the run-up to the U.S. midterm elections, some politicians continue to ride the wave of what’s known as “Christian nationalism” in ways that are increasingly vocal and direct.

GOP Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, a far-right Donald Trump loyalist from Georgia, told an interviewer on July 23, 2022, that the Republican Party “need[s] to be the party of nationalism. And I’m a Christian, and I say it proudly, we should be Christian nationalists.”

Similarly, Rep. Lauren Boebert, a Republican from Colorado, recently said, “The church is supposed to direct the government. The government is not supposed to direct the church.” Boebert called the separation of church and state “junk.”

Many Christian nationalists repeat conservative activist David Barton’s argument that the Founding Fathers did not intend to keep religion out of government.

As a scholar of racism and communication who has written about white nationalism during the Trump presidency, I find the amplification of Christian nationalism unsurprising. Christian nationalism is prevalent among Trump supporters, as religion scholars Andrew Whitehead and Samuel L. Perry argue in their book “Taking Back America for God.”

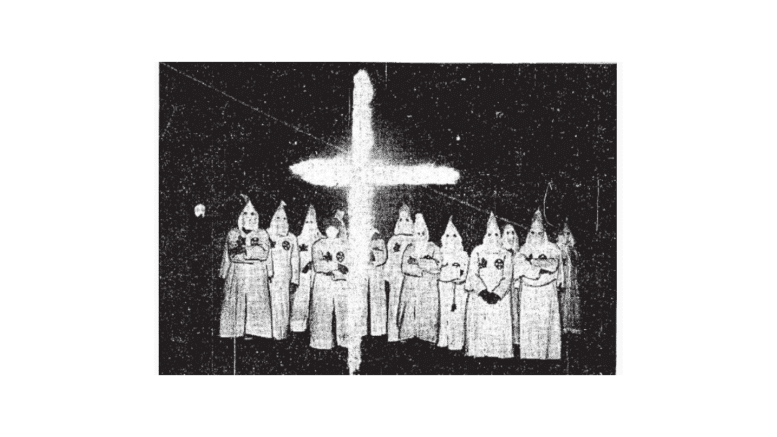

Perry and Whitehead describe the Christian nationalist movement as being “as ethnic and political as it is religious,” noting that it relies on the assumption of white supremacy. Christian nationalism combines belief in a particular form of Christianity with nativist and populist political platforms. American Christian nationalism is a worldview based on the belief that America is superior to other countries, and that that superiority is divinely established. In this mindset, only Christians are true Americans.

Parts of the movement fit into a broader right-wing extremist history of violence, which has been on the rise over the past few decades and was particularly on display during the Capitol attack on Jan. 6, 2021.

The vast majority of Christian nationalists never engage in violence. Nonetheless, Christian nationalist thinking suggests that unless Christians control the state, the state will suppress Christianity.

From siege to militia buildup

Violence perpetrated by Christian nationalists has manifested in two primary ways in recent decades. The first is through their involvement in militia groups; the second is seen in attacks on abortion providers.

The catalyst for the growth of militia activity among contemporary Christian nationalists stems from two events: the 1992 Ruby Ridge standoff and the 1993 siege at Waco.

At Ruby Ridge, former Army Green Beret Randy Weaver engaged federal law enforcement in an 11-day standoff at his rural Idaho cabin over charges relating to the sale of sawed-off shotguns to an ATF informant investigating Aryan Nation white supremacist militia meetings.

Weaver ascribed to the Christian Identity movement, which emphasizes adherence to Old Testament laws and white supremacy. Christian Identity members believe in the application of the death penalty for adultery and LBGTQ relationships in accordance with their reading of some biblical passages.

During the standoff, Weaver’s wife and teenage son were shot and killed before he surrendered to federal authorities.

In the Waco siege a year later, cult leader David Koresh and his followers entered a standoff with federal law enforcement at the group’s Texas compound, once again concerning weapons charges. After a 51-day standoff, federal law enforcement laid siege to the compound. A fire took hold at the compound in disputed circumstances, leading to the deaths of 76 people, including Koresh.

The two events spurred a nationwide militia buildup. As sociologist Erin Kania argues: “Ruby Ridge and Waco confrontations drove some citizens to strengthen their belief that the government was overstepping the parameters of its authority. … Because this view is one of the founding ideologies of the American Militia Movement, it makes sense that interest and membership in the movement would sharply increase following these standoffs between government and nonconformists.”

Distrust of the government blended with strains of Christian fundamentalism have brought together two groups with formerly disparate goals.

Christian nationalism and violence

Christian fundamentalists and white supremacist militia groups both figured themselves as targeted by the government in the aftermath of the standoffs at Ruby Ridge and Waco. As scholar of religion Ann Burlein argues, “Both the Christian right and right-wing white supremacist groups aspire to overcome a culture they perceive as hostile to the white middle class, families, and heterosexuality.”

Significantly, in 1995, Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh and accomplice Terry Nichols cited revenge for the Waco siege as a motive for the bombing of the Alfred Murrah federal building. The terrorist act killed 168 people and injured hundreds more.

Since 1993, at least 11 people have been murdered in attacks on abortion clinics in cities across the U.S., and there have been numerous other plots.

They have involved people like the Rev. Michael Bray, who attacked multiple abortion clinics. Bray was the spokesman for Paul Hill, a Christian Identity adherent who murdered physician John Britton and his bodyguard James Barrett in 1994 outside of a Florida abortion clinic.

In yet another case, Eric Rudolph bombed the 1996 Atlanta Olympics. In his confession, he cited his opposition to abortion and anti-LGBTQ views as motivation to bomb Olympic Square.

These men cited their involvement with the Christian Identity movement in their trials as motivation for engaging in violence.

Mainstreaming Christian nationalist ideas

The presence of Christian nationalist ideas in recent political campaigns is concerning, given its ties to violence and white supremacy.

Trump and his advisers helped to mainstream such rhetoric with events like his photo op with a Bible in Lafayette Square in Washington following the violent dispersal of protesters, and making a show of pastors laying hands on him. But that legacy continues beyond his administration.

Candidates like Doug Mastriano, the Republican gubernatorial candidate in Pennsylvania who attended the Jan. 6 Trump rally, are now using the same messages.

In some states, such as Texas and Montana, hefty funding for far-right Christian candidates has helped put Christian nationalist ideas in the mainstream.

Blending politics and religion is not necessarily a recipe for Christian nationalism, nor is Christian nationalism a recipe for political violence. At times, however, Christian nationalist ideas can serve as a prelude.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on Jan. 15, 2021.

Samuel Perry, Associate Professor, Baylor University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.