by Melissa Hellmann, Center for Public Integrity

This article was originally published by the Center for Public Integrity, a nonprofit investigative news organization based in Washington, D.C.

December 9, 2022

PHILADELPHIA — In the second year of J. Jondhi Harrell’s 20-year sentence, he began to contemplate what would alter a person’s life for good. Financial literacy, employment, mentorship and community support were essential, he recalled thinking.

“If you can’t feed yourself, if you can’t manage your money, you can’t build a solid foundation for the future,” Harrell said in the lobby of the First African Baptist Church, 13 years after completing his sentence.

That morning in late November, his organization, TCRC Community Healing Center, gave away dried fruit, nuts, 170 turkeys and 100 chickens to more than 370 families on the church’s sidewalk. Many of the visitors that day were impacted by the prison system in some way — either because they or their loved ones had been incarcerated.

As the organization’s founder and executive director, Harrell sees how safe and thriving communities can help build a strong foundation upon reentry.

Each year, the more than 600,000 people released from state and federal prisons nationwide face a range of financial barriers. Difficulty accessing banking, a lack of credit, court fines and fees and dismal employment opportunities are common challenges. Together they can have devastating consequences for individuals and families, researchers say.

Barriers to reentry are particularly relevant in Philadelphia, where nearly a quarter of residents live below the poverty line. While Philadelphians make up 12% of Pennsylvania’s population, they’re 26% of the Commonwealth’s prison population.

Tony Lowden, former executive director of the Federal Interagency Council on Crime Prevention and Improving Reentry, recalls seeing his neighbors in North Philadelphia return from prison as a youth. They couldn’t get a job or even an interview due to their criminal record. Predatory lenders took advantage, knowing formerly incarcerated people had difficulty accessing traditional banking services, he said.

“With all these barriers that a person has coming back into the community, rolling up in the inner city communities or rural communities where there’s no financial literacy in those areas, they end up becoming justice-involved: desperate people doing desperate things,” he said.

Lowden vowed to do everything he could to ensure that formerly incarcerated people could earn a living wage and create financial stability in areas like his childhood neighborhood, where the odds were stacked against them.

Now as the vice president of reintegration and community engagement at ViaPath Technologies, Lowden works to provide free educational courses and training on topics including job skills, math and language arts, personal growth and finance on tablets for people in prison and upon their reentry. The company’s services are in 64 of the largest correctional facilities in the nation, where Lowden said they serve around 1.2 million incarcerated people.

Just as Lowden witnessed as a youth, formerly incarcerated people still face discrimination and stigma in the labor market. Some states even preclude people with criminal records from obtaining occupational licenses, such as for nurses or veterinary technicians.

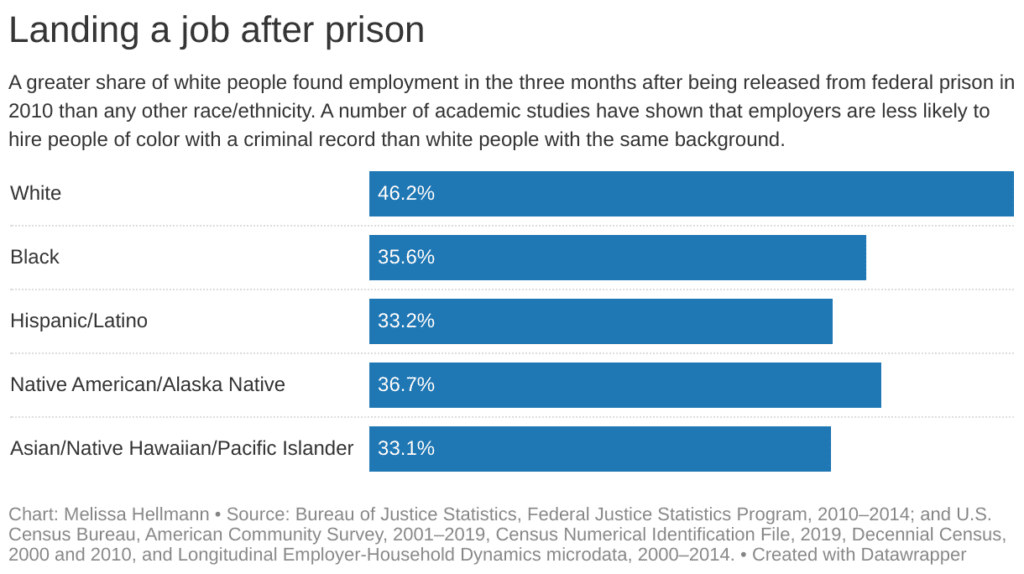

A 2021 Bureau of Justice Statistics study looked at the employment of 51,500 people released from federal prison in 2010. A third found no jobs in the four years post-release.

For those in the study who did find employment, it took them an average of more than six months, according to the report. People of color fared the worst, with Native Americans spending over eight months to find work, compared to white people at around five months.

Job prospects are particularly important upon reentry, since people are less likely to return to prison when they have full-time employment.

Terry-Ann Craigie, associate professor of economics at Smith College and an economic fellow at Brennan Center for Justice, where she focuses on the intersection of race, labor and mass incarceration, said the economic impact is massive. Over a lifetime, people who were imprisoned earn half a million dollars less on average than people who were not.

But Craigie believes the current job market offers some good news for job seekers who were previously imprisoned.

“Because of the economic climate we’re in, we’re seeing that unemployment is really … low,” said Craigie. When it’s harder for employers to fill openings, “you would expect that people with criminal records or formerly incarcerated people probably stand a better chance of getting hired.”

Another barrier: financial obligations in the form of fines, supervision fees, court costs, property forfeitures and restitution to victims. A 2017 Harvard Kennedy School report found that financial obligations can “have long-term effects that significantly harm the efforts of formerly incarcerated people to rehabilitate and reintegrate, thus compromising key principles of fairness in the administration of justice in a democratic society and engendering deep distrust of the criminal justice system among those overburdened by them.”

“Tough on crime” policies, including mandatory minimum sentencing and harsher punishments for defendants with repeat convictions, fueled mass incarceration in the 1980s and ’90s. With that came rising costs to sustain the system. Fines and fees increased.

The justice system’s operational costs rose nationally from $84 billion in 1982 to $265 billion in 2012, adjusted to account for inflation, according to The Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority. The number of incarcerated people facing fines tripled to 37% between 1986 and 2004.

Racial disparities in policing and sentencing mean that fines and fees disproportionately impact Black families.

Hakeem Rudd, pantry manager for TCRC Community Healing Center, met Harrell in the Atlanta Penitentiary in the mid-2000s. Rudd said that he’s seen people return to criminal activity to pay for their fines and fees upon release. A 2015 survey by community researchers across 14 states found that formerly incarcerated people have an average debt of $13,607 in fines and fees.

“You served your time,” Rudd said. “You’re putting people back in the line of fire because you’re sending them home with a bill.”

Penalties for not paying fines and fees can have debilitating consequences and perpetuate cycles of poverty, studies show. While laws on criminal justice debt vary by state, driver’s license suspension, accrued interest from private debt collectors, lowered credit scores, tax refund forfeiture, re-incarceration and increased parole time are common results for people who cannot pay.

It can also lead to disenfranchisement. A Florida law denies voting rights to an estimated 934,500 formerly incarcerated people due to outstanding fines and fees, according to The Sentencing Project.

Louisiana is the only state where court debt is not a barrier for expungement, a legal process that removes a conviction from a person’s criminal record. That’s according to a recent National Consumer Law Center and Collateral Consequences Resource Center study.

Some states and jurisdictions allow fines and fees to be waived or community service ordered in lieu of payment when people can’t pay.

Across the nation, states are lifting restrictions related to unpaid fines and fees and removing other financial barriers for formerly incarcerated people. Colorado, Delaware and Nevada are among several states in recent years to prohibit the suspension of driver’s licenses for nonpayment of criminal debt. The federal Driving for Opportunity Act wending through Congress would incentivize other states to follow suit.

A recently passed law in Washington, D.C., ensures that outstanding criminal debt does not prevent a sentence from being completed, while an Illinois act bans courts from denying requests to expunge or seal a record due to nonpayment of fines and fees.

On the job front, 37 states — and some cities, including Philadelphia — have adopted “ban the box” laws by disallowing criminal history questions on job applications. A federal law that took effect last year prohibits federal contractors from inquiring about an applicant’s criminal record prior to a job offer. Additionally, reforms to occupational licensing laws in 39 states and D.C. since 2015 have made it easier for people with criminal records to work in fields that require licenses.

Back in Philadelphia, Harrell stood in the bright sun as he distributed food in between a steady stream of cell phone calls about the pantry operations. His organization has focused on food security since the brick-and-mortar center closed due to the pandemic in 2020.

This fall, TCRC Community Healing Center began leasing a building from a church. Along with the food pantry, the center helps returning citizens reintegrate into society by referring them to organizations that provide guidance on rebuilding their credit, opening bank accounts and finding free professional attire.

More than anything, Harrell said he takes pride in offering a space where cheerleading and “encouraging people to see the positive aspects of their reentry” is the norm.

This article first appeared on Center for Public Integrity and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.