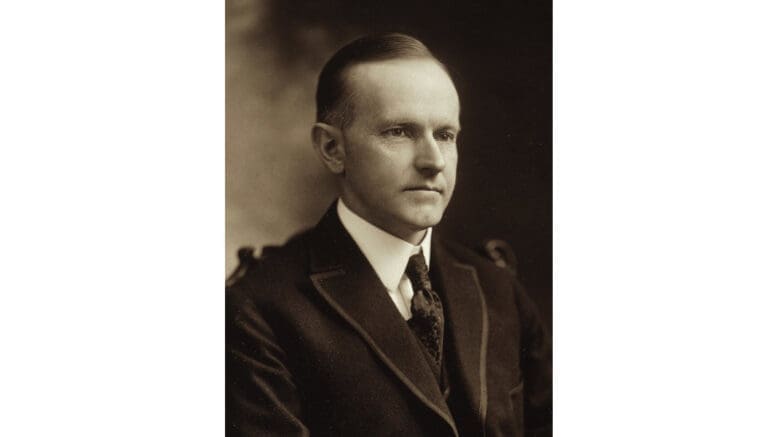

Photo of Calvin Coolidge from Library of Congress — public domain

By John A. Tures, Professor of Political Science, LaGrange College

During the fourth GOP Presidential Debate, each of the four candidates for president chose a different U.S. President to draw inspiration from, and only half were Republicans. While Nikki Haley chose George Washington, Chris Christie took Ronald Reagan and Vivek Ramaswamy opted for Thomas Jefferson, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis selected an unusual choice: Calvin Coolidge. Though conservatives are trying to rehabilitate his image as a great president, the man who occupied the White House from 1923 to 1929 may not be the best choice for America.

“One of the guys I’ll take inspiration from is Calvin Coolidge,” DeSantis said in the Republican debate on NewsNation at the University of Alabama. “Now, people don’t talk about him a lot. He’s one of the few presidents that got almost everything right. He understood the proper role of the federal government under the Constitution.”

DeSantis went on. “We need to restore the U.S. Constitution as the centerpiece of our national life. And that requires a president who understands the original understanding of the Constitution, who has a good sense of the Bill of Rights, and who knows how we’ve gone off track with this massive fourth branch of government, this administrative state which is imposing its will on us and is being weaponized against us. So, silent Cal knew the proper role of the federal government. The country was in great shape when he was President of the United States, and we can learn an awful lot from Calvin Coolidge.”

Coolidge was a remarkable improvement in character from the scandal-plagued Warren G. Harding Administration and personal conduct of the White House occupant from those years. And he was hardly “Silent,” giving a record 520 press conferences in just under six years, as well as a monthly radio address. And he has his support among some authors. Yet when it came time for action and heading off future disaster, Coolidge came up well short of what this country really needed in the 1920s.

“It became apparent that his policies contributed to the stock market crash of 1929 and the Great Depression that followed,” writes Rutgers Professor David Greenberg for the Miller Center. “His fiscal policy encouraged speculation and ignored inequality, as the flow of dollars into the pockets of the wealthy helped tip the healthy investment of the mid-1920s into the gambling that followed. His hands-off regulatory policy took its toll especially in the financial arena, where the dangerous practice of margin trading was allowed to flourish unrestrained. And for all the heady growth of the 1920s, Coolidge’s policies exacerbated the uneven distribution of income and buying power, which led to the overproduction of goods for which there were not enough affluent consumers.”

In fact, there is a vast amount of scholarship that connects Coolidge to America’s disastrous depression, that occurred in the same year in which he left office. In The Independent Review, Thomas Tacoma writes “Niall Palmer repeats the overproduction/underconsumption thesis and suggests that Coolidge was should have been active in rectifying the situation. In a substantive contribution, he notes that Coolidge was in fact aware of the dangerous stock speculation in 1928 and 1929, but concludes that ‘even had he been philosophically inclined to intervene, he lacked the confidence to challenge the optimistic forecasts of leading economists, such as Professor Irving Fisher of Yale, of Wall Street bankers, and of the administration’s own economic policy advisors.’ This was Coolidge’s own fault, Palmer explains, because he had appointed all of these premarket officials to their government positions. When he found himself disagreeing with their ideas, he also discovered he was unable to contend with them.” That the President could foresee the disaster, but unfortunately felt compelled to stay silent and do nothing.

Then there’s the farm depression, which preceded the stock market crash by several years. “Congress passed versions of the McNary-Haugen bill twice, but Coolidge vetoed them,” Greenberg added. “Still he failed to champion any alternative legislation, thus worsening the farm crisis when the Great Depression struck.”

Our Founding Fathers were wise enough to create a constitution that could be changed, and a legislature that could make new laws to face new crises that the crafters of government could not yet envision. Coolidge chose a 1700s governing philosophy, even when he could see disaster before him, choosing an outdated ideology over a pragmatic solution. And Florida’s governor should pick a new presidential role model.

John A. Tures is a professor of political science at LaGrange College in LaGrange, Georgia. His views are his own. He can be reached at jtures@lagrange.edu. His Twitter account is JohnTures2.