by Jonathan Este, The Conversation, [This article first appeared in The Conversation, republished with permission]

While it may seem glib to repeat the notion of a new cold war, winter 2023-2024 has brought with it the sense that there is now an ever-more uncertain faultline between the west and an increasingly aggressive Russia – perhaps more vividly than at any time since the late 1980s. While it is considered a given that a united and determined response from Nato would have the capacity to outgun Russia in the event of the war in Ukraine escalating, US military planners need to factor in the need to maintain a sufficient deterrent force to counter any Chinese moves on Taiwan.

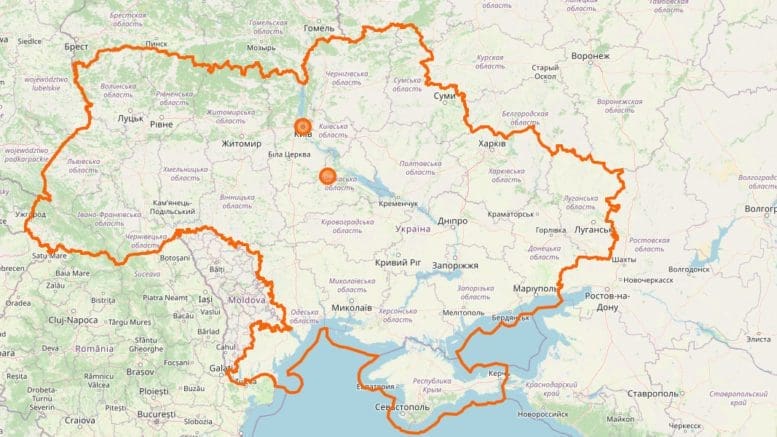

All of which increases the stakes in Ukraine. If Russia were to conquer the whole of Ukraine (remembering it already effectively controls neighbouring Belarus), its border with Nato would extend across Poland, Hungary, Slovakia and Romania. Moldova, which – while having cordial relations with Nato is not a member, so not protected by the group’s mutual self-defence principle – would be more exposed. There have already been attempts to destabilise the country via the Russian separatist enclave of Transnistria.

These are the harsh realities that the Nato as a whole – as well as the US and the European Union separately – must confront as members debate the extent to which they will continue to supply Ukraine with armaments. They will be conscious that Russia has ramped up its military production significantly, allocating one-third of its 2024 budget to defence spending. Meanwhile both the US and the EU are deeply divided over continuing to supply Kyiv with the weapons it needs.

In his end-of-year press conference this week, Volodymyr Zelensky called for a further 500,000 new troops next year. But the concern is that they will have nothing to fight with, given the struggles going on both within the US congress and the EU to pass bills to provide more than £100 billion in further aid for Kyiv.

Stefan Wolff of the University of Birmingham and Tetyana Malyarenko of the University of Odesa believe the key for Ukraine in 2024 will be to hold their lines and prevent Russia from occupying any more territory, while they train their new conscripts. This would give Kyiv’s western allies an opportunity to find a way around the roadblock in funding Ukraine’s war effort.

Neither Ukraine nor Russia have rowed back on their war aims. Zelensky stressed that his ten-point peace plan was the only acceptable position, while Vladimir Putin, in his own end-of-year press conference, insisted that his plan was still “denazification, demilitarisation and a neutral status for Ukraine”. That Putin held a press conference at all is an indication he thinks Russia’s position is more favourable than it was this time last year, when he didn’t.

Accordingly, it was a bullish Russian president who fronted up for a four-hour combined press conference and phone-in. It made for required viewing for Russian television audiences, in that it appeared on every network. Precious Chatterje-Doody, an expert in international affairs from the Open University, says that despite questions such as “Tell us, when will our lives get better?” and “Hello, How can one move to the Russia that they talk about on Channel One?”, the affair was clearly carefully stage-managed to give the impression of a leader who is in complete control and confident of success.

And, with an economy that looks to be in pretty robust shape and an approval rating north of 80%, he can afford to be, she writes here.

Zelensky was recently in Washington to plead Ukraine’s case for continuing US backing. But he had to leave empty handed for now after meetings at the White House and a closed-door sessions with senators as well as Republican House leader, Mike Johnson. “I admire him, but he didn’t change my mind at all about what we need to do,” Republican senator Lindsey Graham told the BBC. “I know what needs to happen to get a deal. I want to secure our border.”

Jessica Trisko Darden, an associate professor of political science at Virginia Commonwealth University has the background on the US aid roadblock and what Ukraine might need to do to overcome it.

Nato divisions

When Zelensky arrived in Washington, Republican congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene made her position clear on X (formerly Twitter): “With Zelensky in town and Ukraine money running dry, why doesn’t anyone in Washington talk about a peace treaty with Russia??” she tweeted. “A deal with Putin promising he will not continue any further invasions. Answer: Washington wants war, not peace. Isn’t that awful?! I’m still a NO.”

Setting aside the fact that Putin had already invaded Georgia, years before he sent his war machine into Ukraine and has broken a host of treaties in recent years, Greene also seems blissfully unaware that the4 vast majority of funding earmarked for military aid to Ukraine stays in the US and pays for US military materiel which is used to degrade Russia’s military capabilities.

But the possibility of years of increased defence spending is certainly putting pressure on Ukraine’s western allies, writes Kenton White, an expert in strategic studies and international relations at the University of Reading. Apart from anything else, the arms already donated to Kyiv have come close to exhausting the production capacity of Nato member states. (Apparently the number of Javelin missiles sent by the US to Ukraine in the first six months of the war represented seven years of regular production.)

The EU is also experiencing difficulties in getting its own aid package through. Hungary is the main stumbling block here. Hungary’s president, Viktor Orbán, is firmly in Putin’s camp and is not only wielding his country’s veto when it comes to the €50 billion (£25.7 billion) EU financial package for Ukraine, but has signalled he will make trouble for Ukraine when it comes to joining the EU.

Last week he “left the room” when the European Council voted to begin accession talks with Kyiv. But, as Stefan Wolff writes, these talks are likely to last a decade or more and will be subject to the final agreement of all member states. Still, Wolff believes that the EU will find a way of “working around” the barriers put up by Hungary and the fact that it has signalled it wants Ukraine in the tent cannot but be a fillip for Zelensky at a time of uncertainty.

Luigi Lonardo, an expert in EU legal matters at University College Cork, meanwhile. details the military, economic and political imperatives facing Kyiv next year, as well as some key issues that could affect continuing western support.

Lonardo spells out the clear European interest in preventing Russia from seizing any more territory in Ukraine and points to the critical need for countries such as Slovakia and Hungary, which have signalled they may not continue to support EU aid for Kyiv, to fall into line with the majority of members. Without EU support, he says, and in the event Donald Trump wins office at the end of the year and cuts off US military backing, Ukraine’s prospects for regaining control of its pre-2014 borders look all but impossible.

Putin’s popularity

Meanwhile Putin’s polling numbers remain strong. According to Russian research institute the Levada Center, the president’s approval rating is 85%, while in September the war in Ukraine received an approval rating northwards of 70%. Of course, it’s tempting to assume that you can’t trust opinion polling coming out of Russia, but – as Alexander Hill, a Russia specialist from the University of Calgary notes – Levada is deemed a “foreign agent” by the Russian government. And its results are backed by other polling organisations.

As already noted, Russia’s economy has handled the western sanctions remarkably well, news from the battlefield is a great deal better than it was this time last year and of course there’s a “rally round the flag” effect you’d expect in any country. That and the fact that the media is now almost completely under the control of the Kremlin.

So when Putin runs for election for a fifth term of office early next year, you’d get pretty short odds on him winning again. His strategy is straight out of the autocrats’ playbook. Rule number one: first eliminate the opposition.

It was with this principle in mind no doubt that Putin had dissident politician Alexei Navalny poisoned in 2020 and then arrested when he returned to Russia in 2021. Navalny has since been found guilty of an array of charges, the most recent of which was “extremism”, which carries a sentence of 19 years. Added to the sentences he was already serving, this leaves him facing more than three decades inside.

If he survives that is. At present nobody seems to know where Navalny is after he is reported to have disappeared a fortnight ago, leading to speculation he may have been done away with. Kevin Riehle, an expert in intelligence and security at Brunel University London, thinks it more likely that Navalny has been transferred to a more remote and secure prison complex where his contact with the outside world will be minimal.

But as Riehle concedes, Putin’s opponents have a habit of coming off badly and the more prominent the opponent, the worse fate they can expect.

Ukraine Recap is available as a fortnightly email newsletter. Click here to get our recaps directly in your inbox.

Jonathan Este, Senior International Affairs Editor, Associate Editor, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.