by Jennifer Shutt, Georgia Recorder, [This article first appeared in the Georgia Recorder, republished with permission]

November 27, 2024

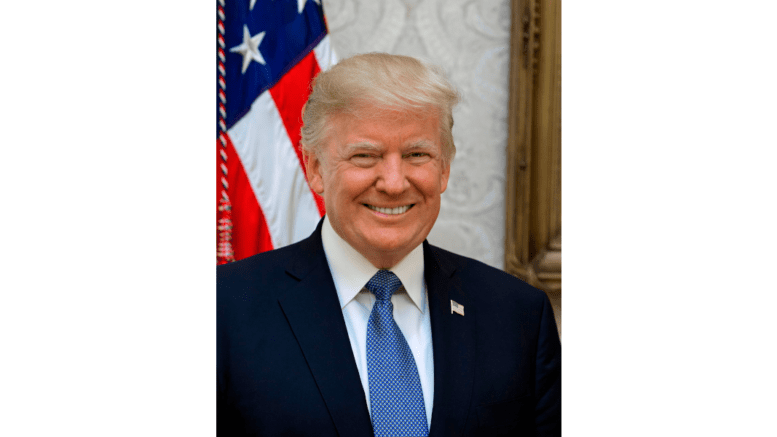

WASHINGTON — President-elect Donald Trump said Tuesday he has selected a Stanford University professor of health policy and skeptic of COVID-19 precautions to run the National Institutes of Health, the sweeping federal agency tasked with solving many of the country’s biggest health challenges.

Dr. Jay Bhattacharya will require Senate confirmation before taking over the role officially, but assuming he can secure the votes next year when the chamber is controlled by Republicans, he’ll have significant sway over where the federal government directs billions in research dollars.

“Dr. Bhattacharya will work in cooperation with Robert F. Kennedy Jr. to direct the Nation’s Medical Research, and to make important discoveries that will improve Health, and save lives,” Trump wrote in the announcement. Kennedy is Trump’s pick to lead the Department of Health and Human Services.

Bhattacharya posted on social media that he was “honored and humbled” by the nomination and pledged to “reform American scientific institutions so that they are worthy of trust again and will deploy the fruits of excellent science to make America healthy again!”

In addition to Kennedy, other Trump nominees for health-related positions include former TV personality and onetime Pennsylvania U.S. Senate candidate Mehmet Oz to lead the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, former Florida Congressman Dave Weldon to run the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Dr. Marty Makary for commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration and Fox News medical contributor Dr. Janette Nesheiwat as the next surgeon general.

“Together, Jay and RFK Jr. will restore the NIH to a Gold Standard of Medical Research as they examine the underlying causes of, and solutions to, America’s biggest Health challenges, including our Crisis of Chronic Illness and Disease,” Trump wrote in his announcement.

Health economist

Bhattacharya received his undergraduate degree from Stanford University in 1990 before earning his medical degree from its School of Medicine in 1997 and a Ph.D. from the university’s Economics Department in 2000.

He focuses his research on health economics and outcomes, according to his curriculum vitae, the academic version of a resume.

Bhattacharya’s biography on Stanford’s website says that in addition to being a professor of health policy, he runs its Center for Demography and Economics of Health and Aging, in addition to working as a research associate at the National Bureau of Economics Research.

“Dr. Bhattacharya’s research focuses on the health and well-being of vulnerable populations, with a particular emphasis on the role of government programs, biomedical innovation, and economics,” according to the biography.

Among his research areas is the “epidemiology of COVID-19 as well as an evaluation of policy responses to the epidemic.”

‘A fringe component’

Bhattacharya testified before the U.S. House Oversight Committee’s Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Pandemic in February 2023 that he believed there was “near universal agreement that what we did failed.”

“Official counts attribute more than one million deaths in the United States and seven million worldwide,” he said.

Bhattacharya was one of three authors of The Great Barrington Declaration in October 2020, arguing that younger, healthy people should have gone about their normal lives in an effort to contract COVID-19, since they were somewhat less likely to die than at-risk populations.

The brief declaration says that “(a)dopting measures to protect the vulnerable should be the central aim of public health responses to COVID-19.” But it doesn’t list what those measures should include and never brings up masking, physical distancing, or vaccination.

Several public health officials and researchers rejected the declaration, noting that it didn’t cite any research, data or peer-reviewed articles.

Former NIH Director Francis S. Collins, who ran the agency from 2009 through 2021, told The Washington Post in October 2020 that the Barrington Declaration authors’ beliefs were not held “by large numbers of experts in the scientific community.”

“This is a fringe component of epidemiology. This is not mainstream science. It’s dangerous. It fits into the political views of certain parts of our confused political establishment,” Collins said in the Post interview. “I’m sure it will be an idea that someone can wrap themselves in as a justification for skipping wearing masks or social distancing and just doing whatever they damn well please.”

One of the many reasons public health experts recommended masking, working from home and physical distancing before there was a COVID-19 vaccine was to prevent patients from overwhelming the country’s health care system.

There were concerns during some of the spikes in COVID-19 infections that the country would have so many ill people at one time there wouldn’t be enough space, health care professionals or equipment to provide treatment.

Wide-ranging agency

The NIH is made up of 27 different centers and institutes that each focus on health challenges facing Americans.

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, formerly run by Dr. Anthony Fauci, became one of the more well known institutes during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially when he would regularly appear beside Trump at press briefings.

Other components at NIH include the National Cancer Institute, National Institute on Aging, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the NIH Clinical Center that’s also referred to as America’s research hospital.

Congress approved $48 billion in discretionary spending for NIH during the last fiscal year, continuing a broadly bipartisan push that for years has increased funding to the agency to provide grants to research some of the most challenging diseases and illnesses facing Americans.

The current NIH director, Monica M. Bertagnolli, testified before Congress in early November about how the agency was working to rebuild trust following the pandemic.

Bertagnolli told U.S. House lawmakers the NIH was focusing some of its research on finding cures for rare diseases, since for-profit companies often don’t have the financial incentive to do so.

She also rejected the notion that NIH leaders have allowed politics to interfere with the agency’s mission.

“First and foremost, NIH concentrates on science, not on politics,” Bertagnolli said. “We actually have an integrity mandate against political interference in our work. That is the law for us and we abide by that completely.”

Last updated 10:53 a.m., Nov. 27, 2024

Georgia Recorder is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Georgia Recorder maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor John McCosh for questions: info@georgiarecorder.com. Follow Georgia Recorder on Facebook and X.