by Thomas A. Durkin, Loyola University Chicago and Joseph Ferguson, Loyola University Chicago, [This article first appeared in The Conversation, republished with permission]

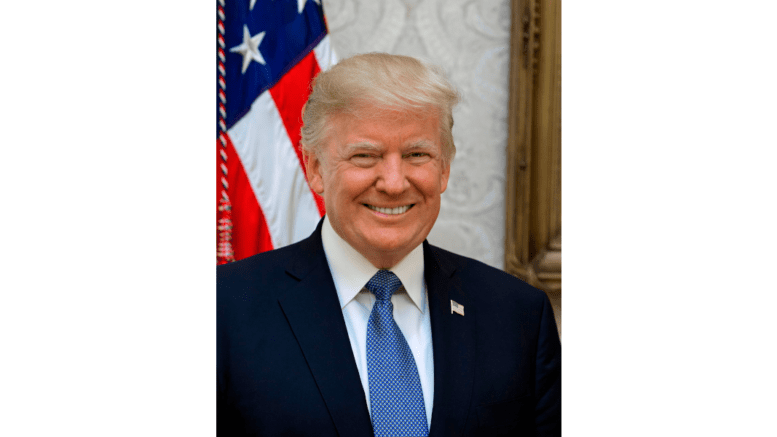

Lawyer Thomas A. Durkin has spent much of his career working in national security law, representing clients in a variety of national security and domestic terrorism matters. Joseph Ferguson was a national security prosecutor in the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Northern District of Illinois, where Durkin was also a prosecutor. Both teach national security law at Loyola University, Chicago. The Conversation U.S.‘s democracy editor, Naomi Schalit, spoke with the two attorneys about the federal indictment of former President Donald Trump on Espionage Act and other charges related to his retention of national security-related classified documents.

The word “weaponized” has been used by Trump, his supporters and even his GOP rivals to describe the Department of Justice. Do you see the Trump prosecution as different in any notable way from other Espionage Act prosecutions that you’ve worked on or observed?

Durkin: Obviously, it’s different because of who the defendant is. But I see it in kind of an opposite way: If Trump were anyone other than a former president, he would not have been given the luxury of a summons to appear in court. There would be a team of armed FBI agents outside his door at 6:30 in the morning, he would have been arrested and the government would be immediately moving to detain. So the idea that he’s being treated differently is true – but not from the way his supporters seem to be arguing.

Ferguson: What you have is a method, manner and means of pursuing this matter and bringing it forward to indictment that actually completely comports with the deepest traditions and standards of the Department of Justice, which would normally consider all contexts and the best interests of society.

If Trump were your client, what would you advise him to do?

Durkin: The first thing I would do is show him a guidelines memo, which we typically create for every client to help them understand the potential consequences of the charges. Under the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines, the consequences for Trump under this indictment are serious. My quick calculations indicate that you’re talking about 51 to 63 months in the best case and in the worst case, which I’m not sure would apply, 210 to 262 months.

Whether he wants to roll heavy dice, that’s up to him. But those are very heavy dice.

Ferguson: I might pull media statements that he has made in the last couple years and explain to him how they have complicated the ability to defend him. I’d put on the table to him that I need to see every statement that he is going to make in the political realm about this before he makes it. I’d tell him he’s otherwise basically hanging himself.

I’d tell him: If you want to die in jail, keep talking. But if you want to try to figure out a way that brings about an acceptable resolution – a plea deal that opens the door to a lighter jail sentence than what the guidelines threaten and, possibly, even no jail time – you need to turn it down or at least have it screened by your lawyers.

Are there specific things he might say between now and a trial that could deepen his trouble?

Ferguson: No question about that. And people should understand that the things that he said already are being used as evidence of intent. From now on, the repetition of them constitutes new admissible evidence. It’s not like, “Oh, I’ve already said it, so I might as well keep saying it.”

That does not mean that he cannot offer the broad brush characterization, “I’m being wronged. This is the weaponization of law enforcement and the justice system against me, and I will be vindicated,” however imprudent I might think that was. But anything that goes beyond that, and into the actual particulars, referencing the documents themselves, will just make it worse.

The Trump indictment provides extensive details of what was said and done. Do you take those as true, or as allegations that need to be proved?

Ferguson: Both. They are technically the allegations that need to be proven, but when you’re speaking at that level of granularity, these are things that actually exist in proof, the proof that is to come.

The government basically raises the bar when it provides this form of granularity. The federal government is a risk-averse enterprise when it comes to these matters, so nothing is put in the indictment unless it exists in actual fact.

Durkin: If you’re defending someone, you treat the allegations as true.

Can you imagine a situation with all of the facts laid out in this indictment but where they would not indict?

Durkin: No.

Ferguson: That’s why we both say that in fundamental respects, this isn’t different from other national security cases. These cases work from the premise that this is a fundamental compromising of the interests of the United States. And those are the cases that the government pursues tooth and nail. With so much in the public domain, and with so much of the defendant himself speaking to all of this, it almost puts the government in a position of saying, “Well, OK, if we have to, here we go.”

Durkin: There’s only one reason the government could not bring this case, and that’s fear of violence or an attack on the republic. Once you do that, then you might as well close the Department of Justice and forget about any rule of law.

Trump knows a lot of state secrets. An angry Trump in prison has risks. If he were found guilty, what does incarceration look like for him?

Durkin: I can tell you what it would mean to anyone else. They’d be put in a hole in the wall in maximum security at Florence, Colorado, and they would apply what’s called “Special Administrative Measures.” Several of my terrorism clients have had those imposed on them. There’s a microphone outside their solitary confinement to monitor anything that they say, even between prisoners. Their mail is extremely limited. Their telephone contact is extremely limited. And that’s what would happen to anyone else similarly situated.

Ferguson: Trump’s insistence on keeping talking about this creates a record that would justify isolation in maximum security on the basis that “We can’t trust this man not to continue to talk. We can’t trust him not to further share these secrets with people who may wish to do harm with them. The only way to avoid that is to put him in isolation in supermax where he doesn’t get to talk with people, except under these extremely closely monitored circumstances, certainly isn’t in a general population situation, gets to take a walk in a courtyard for one hour out of the 24 hours of the day, and the other 23 hours, leaving him mostly without human contact.”

Is there a specific line he could cross that would force the government to seek to detain him prior to trial?

Durkin: I predict that if he keeps it up, and especially if he keeps suggesting or threatening violence, that the government will be put in a position where they don’t have a choice but to try to move to detain him. In the real world, that’s what would happen if it was anybody but him. Normally, you can’t be threatening this type of stuff without being put in detention.

Ferguson: The smart play here would be for a judge to put him under a gag order that instructs him on what he may and may not say publicly. That’s already been done by a New York judge in the other pending criminal case against Trump. This would be a complicated exercise in balancing First Amendment rights with national security interests.

Thomas A. Durkin, Distinguished Practitioner in Residence, Loyola University Chicago and Joseph Ferguson, Co-Director, National Security and Civil Rights Program, Loyola University Chicago

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.