[This is republication of an article originally published in the Courier in June of 2017 edited and slightly expanded]

If the first owners of automobiles in Cobb County wanted to drive into neighboring counties, they were faced with a daunting patchwork of complicated and restrictive ordinances, most of them intended to prevent the new contraptions from startling horses.

The state had not yet passed uniform traffic ordinances, and each county enacted rules that seem bizarre by the standards of today’s auto-dominated roads.

Sarah Blackwell Gober Temple reported, in The First Hundred Years: A Short History of Cobb County, in Georgia,

He (the driver) must stop one hundred fifty yards from a horse or mule and stop all noise until the animal had passed at least seventy-five yards; he could not approach nearer than fifty yards nor pass unless the driver or rider gave his consent. He could not approach a horse or mule tied to a post nearer than fifty yards “without the consent of the owner or manager of said horse or mule.” Were he to approach a horse or mule working in a field he must stop within one hundred yards and “and give the person in charge time to unhitch said horse or mule and remove same to a place of safety.” Furthermore, the motorist could not pass any one horse or mule oftener than twice in one day.

Uniform traffic laws and vehicle registration were passed by the state in 1910 to remove the complexity in operating this increasingly popular mode of travel.

But then there were the roads. In the 19th century road-building was a largely communal activity, and the clearing of stumps was not seen as a priority, nor was paving roads. Horses were well suited to going around stumps and walking over dirt roads.

By the turn of the century, each purchase of an automobile in the county was newsworthy, and because of the treacherous road conditions, auto excursions were reported in the press as if the trip were an exploration of the North Pole. The Atlanta Georgian, in June of 1911, reported on a trip from downtown Atlanta to the Sweetwater Park Hotel. The route took the woman driving the car through south Cobb, and was tersely described by the paper as follows:

Automobile route to Sweetwater Park Hotel via North Avenue, Marietta Street to Bellwood avenue, over Chattahoochee bridge, through Mableton, Austell, thence to Lithia Springs. Record time by lady driver — 45 minutes.

In modern terms, most of the route was along what is now Highway 78 (Donald Hollowell Parkway and Veterans Memorial Highway).

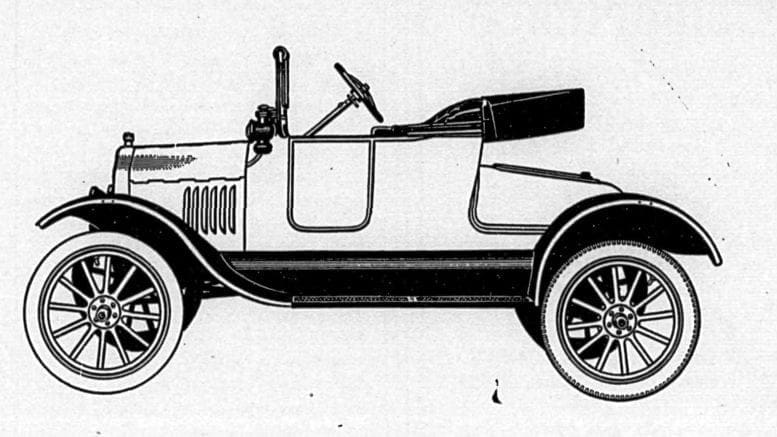

The road improvement movement gathered steam as automobiles became more common. In 1915 there were few paved roads in Georgia and no paved highways. In the late 19th century bicyclists had launched a “Good Roads Movement,” but the effort didn’t take off until 1908 when Ford’s mass-produced cars made automobiles accessible to a larger part of the population.

By 1915 the county had paved a section of road from Marietta to Fair Oaks, but the serious push for paved roads through Cobb County began with the development of the Dixie Highway. An entrepreneur named Carl Fisher had bought most of the property on an island near Miami, Florida, and planned to build a resort. That island is now known as Miami Beach. He began advocating that a north-to-south network of highways be built from Canada to Miami.

The Cobb County section of the Dixie Highway ran along what is now Atlanta Road and Old Highway 41. Even after the highway was designated, sections were still unpaved, and according to Temple’s book, locals created a cottage industry of pulling the automobiles of northern tourists out of the mud.

The progress (and sometimes the lack of progress) was a frequent topic in the local press. On November 26, 1920, the Marietta Journal (one of the earlier names of the current Marietta Daily Journal) ran a front-page article complimenting Smyrna on the job they’d done paving their section of the road.

But the article then stated:

Some three or four short pieces of road between Marietta and Acworth became impassable last winter and will do so again unless they have prompt attention from the county road superintendent.

They are at the city limits, 100 yards at Wilder’s; a mile from town, 200 yards at the Northcutt pasture; some 400 yards at two Noonday crossings; 100 yards at Roberts’ farm, and 200 or 300 yards near the Acworth cotton oil mill.

These short pieces of road make it a nightmare for travelers in winter, interfere with all local traffic, and give Cobb county a black eye.

As federal highway funds became available in the 1920s, sections of the highway were paved, starting with the section from Smyrna to the Chattahoochee River.

Then the section from Acworth to the previously paved portion was completed. By 1929, the road was paved the entire length of Georgia. In 1930 Bankhead Highway, now Highway 78/Veterans Memorial Highway, was paved, giving Cobb County two major paved routes.

For the rest of the 20th century, the automobile and other wheeled motorized vehicles were rapidly becoming dominant in the county, and our modern road and highway network began taking shape.

References for this article:

Jackson, Edwin L. “Dixie Highway.” New Georgia Encyclopedia. 07 March 2016. Web. 25 June 2017.

Temple, Sarah Blackwell Gober. The First Hundred Years: A Short History of Cobb County, in Georgia.

Can you tell me what year Sandy Plains Road was first paved?

According to Thomas Scott’s history of Cobb County, Sandy Plains was first paved as a result of a 1946 bond referendum. A bunch of other roads were paved then too.George McMillan was the county commissioner (there was only one at the time).