Photo above: Graham Jagger and Rebecca Sullivan at 15-foot dropoff (by Rebecca Gaunt)

by Rebecca Gaunt

When Rebecca Sullivan purchased a house in Smyrna nine years ago, her two sons could jump over the creek that runs through the back yard. Now she watches the weather forecast with dread, wondering how long she has before she loses her home to what she described as a 30-foot wide raging river, after the storms caused by Hurricane Idalia blew through last August.

Sullivan’s home, built in 1994, is inside the city of Smyrna. The land on the other side of the creek is unincorporated Cobb County. Sullivan is caught between two municipalities, neither of which is offering solutions.

“A while ago, Cobb was looking to introduce a stormwater fee, and when you look at the report on that and the comments that were made when they had the debate on that, the money was going toward projects like this. So Cobb has identified that there is a significant problem like this,” Sullivan’s father, Graham Jagger, told the Courier.

As the creek has grown wider, deeper, and faster, it is no longer possible to jump across, even though her sons are now in high school. When it rains, especially as it did at the end of August, it becomes a brown, rushing river, depositing trash and tree debris everywhere.

“It used to be so pretty,” she said, standing on the deck she no longer enjoys using.

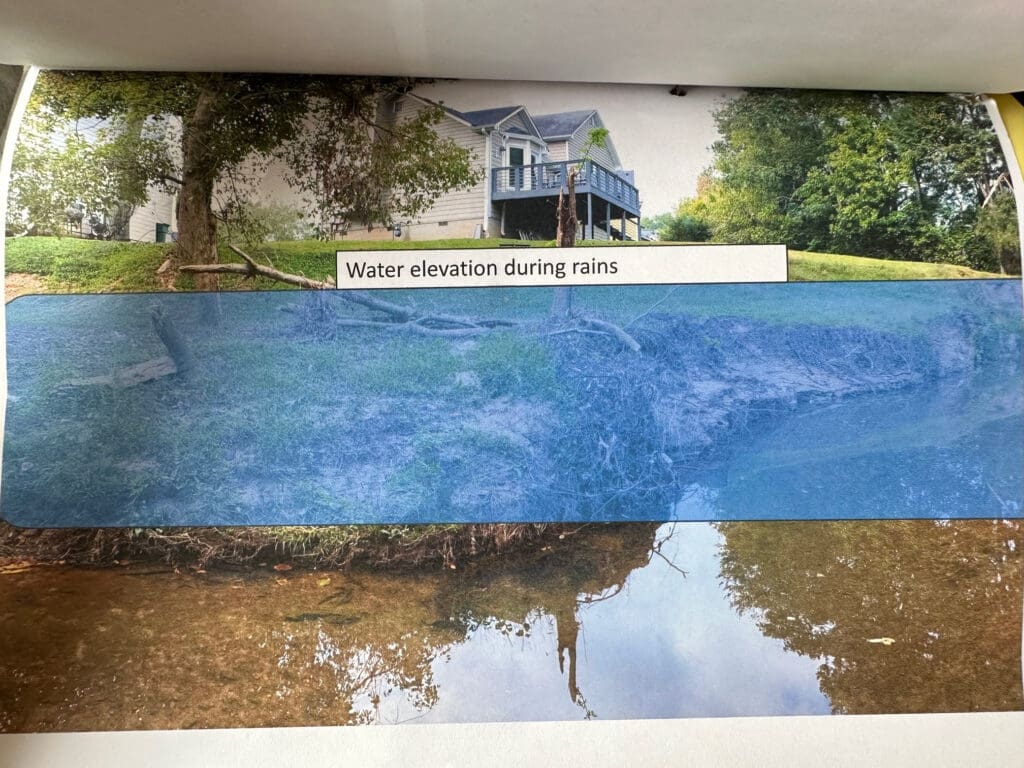

Her yard has eroded by several feet to the water that only comes harder and faster the more the land breaks off into the flow. To the left side of the backyard is a steep dropoff of about 15 feet. To the right, there are stumps where there used to be trees before storms and the subsequent flooding destroyed them. One of the tiny stumps right on the edge of the bank sits cockeyed over the creek. Sullivan planted that tree several years ago. Back then there was enough land that she could walk around it.

That stump disappears under the water if it rains hard enough. In August, the storm also flooded the neighbor’s yard and damaged the fence.

Additionally, there is a city drainage ditch that carries runoff from the city into the creek that runs along the north side of the property. A tire is visible on the bank where the two water flows meet. Jagger and Sullivan said its care falls under the purview of the city.

Jagger lives in Mableton, but after August’s bout of severe weather, he began reaching out to everyone he could think of that might be able to help his daughter, including the city of Smyrna, Cobb County, state legislators, Gov. Brian Kemp, and U.S. Senator Jon Ossoff. The results were initially promising. Local elected officials and city staff came to see the issue in person. Then the mayor’s responses abruptly stopped.

After several email exchanges and a visit to the home, Smyrna Mayor Derek Norton, referred all further communication on the matter to the city attorney Scott Cochran. He did not respond to the Courier’s questions. Nor did Cochran.

Smyrna City Council member Susan Wilkinson also visited the home and Jagger said she truly seemed to want to help. However, he believes the response from the mayor tied her hands.

Wilkinson told the Courier, “I sympathize with them. I just don’t know what we can do.”

She provided additional contacts of city staff who could potentially answer questions about the situation, but none responded.

During one visit, Sullivan said she asked a city of Smyrna official if she was supposed to prepare for financial ruin. His devastating response: yes.

Jagger called the withdrawal of support from the city painful.

Cobb County Commissioner Jerica Richardson also visited the home. In a phone interview, she told the Courier that she has office staff working on a solution, but options are thin. Richardson has ideas about changes that need to be made, but those are long-term solutions that would come too late for Sullivan.

“It’s very complicated. We’ve got gratuities clause laws that prevent local jurisdictions from really doing much of anything that I’m advocating changes to. All the way to federal funds that can’t be specifically designated because they would violate those gratuities clauses. So we’re looking for a way that we can create new types of programs,” she said

Richardson has a staff member currently looking into a grant program that could potentially be used for residential properties and that she hopes might help Sullivan.

“But it’s not a guarantee. It’s a stretch,” she said.

The house being private property, in a flood plain, and in city jurisdiction, means there isn’t a bucket of funds waiting to be utilized.

“This is a full-on change of state law and federal programming,” Richardson said. “I believe the creek itself is county, but there isn’t a responsibility for a creek’s runoff in a flood plain. The house shouldn’t have been built in a flood plain. Those are restricted today, but when the house was built it was not.”

The fact that the house is in a flood plain was not disclosed at the time of purchase, according to Sullivan.

In an email to Commissioner Richardson, state Rep. Teri Anulewicz (D-Smyrna), and Jagger, Mayor Norton asked who held responsibility for paying for the solution, which he estimated at $100,000.

“Mr. Jagger’s point of view is that increased development and impervious surface upstream is responsible for the increased flow and erosion – and I’m sure this is correct to some degree. I just don’t know how to assign responsibility for an equitable solution, especially when we are talking about the ask for public money to be spent on private property,” he wrote.

Jagger disagrees with that framing of the situation.

“The creek – it’s public. It’s somebody else’s. It’s stopping the creek damaging Rebecca’s land,” he said.

Jagger then reached out to U.S. Senator Jon Ossoff. Ossoff’s office assisted by contacting the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Georgia Environmental Protection Division. Both departments sent engineers and environmental specialists to inspect the site.

The USDA, which did a site visit in October, issued a report that notes the 15’ bank is “constantly sluffing off into the creek when rains occur. The left side of the creek as it goes downstream, has a low bank and as the water from the creek rises it spreads out of the left bank and expands. In doing so, debris from the undergrowth is pickled up and carried downstream and leads to further issues. Currently Ms. Sullivan has a few tree stumps/root wads that are holding the bank closer to her house. However, in time those areas will also be removed from the bank.”

Despite that, because there has been no declaration of disaster in the area, Sullivan does not qualify for Emergency Watershed Protection Programs.

“The point it will be declared an emergency is when the house starts to drop off, at which point it’s too late,” Sullivan said.

Georgia EPD did a site visit in late September. According to the report, the loss of surrounding permeable surfaces is a factor, and advised the city of Smyrna to look at stormwater drainage pipes upstream and downstream of the site to determine if there are any obstructions.

The city’s “unmanaged drainage structure” is also listed as a contributing factor to the problem.

Jagger is dismayed that the one elected official who continues to seek a solution might be about to lose her seat. The state Supreme Court is preparing to rule on the county-submitted electoral map after Richardson was drawn out of her district in the 2022 state-drawn map.

Richardson has already announced she plans to run for Congress, but depending on how the court rules, she may not even get to finish her term on the Cobb County Board of Commissioners.

On what needs to be done differently for the future, Richardson said, “It’s thinking forward. We know that we’re gonna see more rainfall. We know that we’re gonna see more flash floods. It’s thinking holistically about disaster recovery.”

One of the surveyors informed Sullivan it’s already affecting her foundation, and she’s desperate for answers.

“It’s a ticking clock,” she said.

Rebecca Gaunt earned a degree in journalism from the University of Georgia and a master’s degree in education from Oglethorpe University. After teaching elementary school for several years, she returned to writing. She lives in Marietta with her husband, son, two cats, and a dog. In her spare time, she loves to read, binge Netflix and travel.